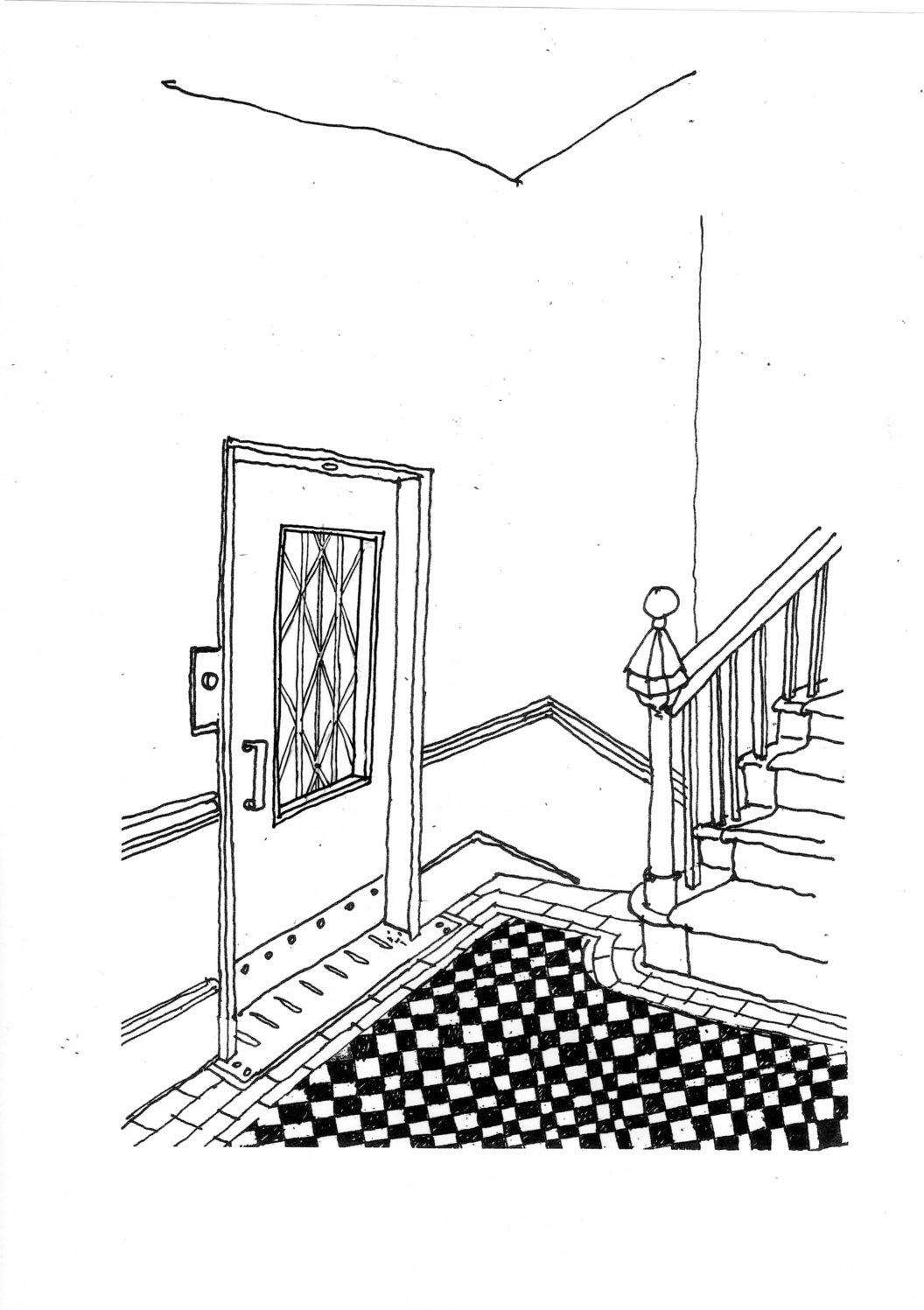

The amazing thing about Nero Wolfe, hero of Rex Stout’s Fer-de-Lance, was that he lived in a house with its own elevator. I was 14 when I first read the book. I was spending the school holidays with my mother and brand-new stepfather, who were then living on an oil pumping station in Iraq with the evocative Babylonian name of K3. The British expatriate staff lived in prefabricated bungalows assembled in various configurations to give the illusion of variety. These were commodious, well-planned and, when the air conditioning worked, comfortable, but characterless. And here was a private detective who lived in an enormous townhouse with its own passenger lift.

Not only that, it had a separate goods elevator to a special orchid-growing house on the roof, and any number of intercoms, alarms, built-in recording devices and electric safes. It even had a gourmet kitchen with its own entrance. Right on Wolfe’s doorstep were a dozen drugstores, delis, dry-cleaners and scores of cinemas. On K3 there was a single weekly showing of an ancient black-and-white film in the outdoor cinema, where, like Eric Morecambe, they played all the right reels but not necessarily in the right order.

Fer-de-Lance is the first in a series of 48 detective novels (or mystery stories as their author styled them). Starting in 1934, when he was 48, Stout spun out an average of one a year until his death in 1975. His hero, Nero Wolfe, is an enormously corpulent man who charges vast sums of money to people who need to hire New York’s finest private investigator – although Wolfe is keen to stress that he is essentially an intuitive artist, not merely a consulting detective. Apart from being huge, or perhaps as a result of being huge, Wolfe likes to move as little as possible, and by the time we are introduced to him he has established a

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inThe amazing thing about Nero Wolfe, hero of Rex Stout’s Fer-de-Lance, was that he lived in a house with its own elevator. I was 14 when I first read the book. I was spending the school holidays with my mother and brand-new stepfather, who were then living on an oil pumping station in Iraq with the evocative Babylonian name of K3. The British expatriate staff lived in prefabricated bungalows assembled in various configurations to give the illusion of variety. These were commodious, well-planned and, when the air conditioning worked, comfortable, but characterless. And here was a private detective who lived in an enormous townhouse with its own passenger lift.

Not only that, it had a separate goods elevator to a special orchid-growing house on the roof, and any number of intercoms, alarms, built-in recording devices and electric safes. It even had a gourmet kitchen with its own entrance. Right on Wolfe’s doorstep were a dozen drugstores, delis, dry-cleaners and scores of cinemas. On K3 there was a single weekly showing of an ancient black-and-white film in the outdoor cinema, where, like Eric Morecambe, they played all the right reels but not necessarily in the right order. Fer-de-Lance is the first in a series of 48 detective novels (or mystery stories as their author styled them). Starting in 1934, when he was 48, Stout spun out an average of one a year until his death in 1975. His hero, Nero Wolfe, is an enormously corpulent man who charges vast sums of money to people who need to hire New York’s finest private investigator – although Wolfe is keen to stress that he is essentially an intuitive artist, not merely a consulting detective. Apart from being huge, or perhaps as a result of being huge, Wolfe likes to move as little as possible, and by the time we are introduced to him he has established a routine that enables him to live an agreeable life more or less without having to move at all. Obviously he needs to earn a living, which means taking on cases, which generally means movement, but unless his coffers are virtually empty, he is mostly reluctant to do even that. Wolfe is modelled on the cerebral English detective, and thus has a great brain that needs to be nourished. Unlike his American contemporaries Sam Spade, Lew Harper and Philip Marlowe, Wolfe does not need to solve mysteries by sticking guns in people’s faces, or driving dames around in his convertible, or sorting out uncooperative witnesses with fisticuffs. Wolfe’s brain is nourished by his love of breeding orchids, which he does between 9 and 11 every morning, and between 4 and 6 every afternoon. We English outcasts in K3 would have killed to cultivate a square foot of lawn. Wolfe’s elevator lifts him to the plant rooms on the roof, the domain of Theo Horstmann, one of the three people with whom he shares his vast brownstone house on New York’s West 35th Street. Theo is Wolfe’s gardener/horticulturist/botanist, the begetter and keeper of the sacred Orchidaceae who helps Wolfe to tend, breed, propagate and even hybridize the exotic flora. Horstmann keeps track of other breeders and is constantly on the lookout for seedlings and rare imports. Occasionally, very occasionally, clients are treated to a tour of this private display, and in very rare instances are even made a present of a bloom. It is not absolutely forbidden for Wolfe to be disturbed while cloistered with his plants, but there is no emergency under the sun that will allow him to be called away during the allocated orchid-tending hours. Wolfe’s considerable frame is nourished by Fritz Brenner, his chef and butler, whose culinary reputation ensures that would-be interrogatees can be persuaded to travel great distances when offered the opportunity to sample Wolfe’s table. Fritz manages the kitchen at the bottom of the house and provides an endless supply of gourmet breakfasts, elevenses, lunches, teas, dinners, picnics and late-night snacks. He also looks after Wolfe’s supply of beer. At the beginning of Fer-de-Lance, we discover that Wolfe is cutting down to 10 quarts a day. Thus, quite a large proportion of his waking life is spent taking the tops off, checking the temperature of, pouring the contents from, and discarding the empty bottles that accrue to this ritual, not to mention actually drinking the stuff. It never occurred to me that gaseous American beer might be considered an unusual complement to, say, a Tabasco crayfish and asparagus soufflé. At 14 I was allowed a small glass of beer as a special treat, and here was this chap virtually living on it. Everything else in Wolfe’s life – cars, guns, gumshoe work, snappy dialogue, schmoozing and billing clients, interviewing people and persuading them to visit Wolfe in his brownstone, where they will be relentlessly cross-examined – is dealt with by Wolfe’s wiseacre sidekick, Archie Goodwin. Goodwin is Wolfe’s amanuensis. It is he who writes up the cases, and it is from his viewpoint that the stories are told. Goodwin is 32, fit, a snappy dresser and an orphan. At the time of this story he has been working for Wolfe for five years, although he realizes, as does Wolfe, that one day he will have to leave, grow up and settle down. Archie knows news reporters, beat cops, collection agents and ex-DAs, and can be relied upon to charm female secretaries into divulging information they might more prudently have kept to themselves. Nero Wolfe mysteries provide a distraction at Totleigh Towers, so it should have been no surprise to discover that P. G. Wodehouse and Stout were friends and admirers of one another’s work. The reader enjoys both writers for the same reasons – the familiar cast of characters, the milieu, the period detail, the relentless storytelling and, above all, the style. Wodehouse said that he’d read Stout’s stories many times and so knew what happened, but they continued to give him pleasure because of the way they were told. Like Bertie Wooster writing of Jeeves, Goodwin is in awe of Wolfe’s great brain. Although he is bright and intuitive himself, and knows how the world works, he can never outguess his employer. ‘“You know it for a fact when you are presented with it, Archie, but you have no feeling for phenomena.” After I’d looked up the word phenomena in the dictionary I couldn’t see that he had anything, butthere was no use arguing with him.’ Wholly unlike Wooster, Goodwin is capable, diligent, sassy and all-American. A good man to have with you in a tight spot, and effortlessly (and rather irritatingly) successful with women. Goodwin does the driving, but unlike Wooster, Wolfe virtually never accompanies him, although he supplies an enormous black roadster which he insists is kept in immaculate condition at all times, in case a client needs to be collected. This spends its nights coddled in a garage two blocks away, quite a hike in New York City. In slack periods, collecting and delivering the roadster seems to be the only exercise that Goodwin ever gets. From 1906 to 1908 Stout served in the US Navy, where he was quartered aboard Teddy Roosevelt’s presidential yacht. This would have been years ahead of the White House in terms of the advanced ‘residential’ technology it enjoyed, and the pneumatics, intercoms, air conditioning, communications, food refrigeration and built-in furniture all find their way into the fabric of Wolfe’s brownstone. Early in his career Stout had invented a banking system that enabled schools to manage the individual savings accounts that they encouraged their pupils to open. The system was adopted by several hundred schools across the country, and Stout was paid a royalty. This enabled him to travel around Europe, where he wrote several novels and learned everything about everything, particularly about what was good to eat and the way to tell someone how to make it for him. He lost everything in the stock-market crash of 1929 and so had to return to America and begin writing in earnest. Fer-de-Lance, and with it the Nero Wolfe ensemble, appeared four years later. Wolfe’s pampered and agreeable lifestyle is not cheap, of course. One has no idea about Sherlock Holmes’s finances beyond knowing that he slips his Baker Street irregulars a sixpence from time to time, but Wolfe demonstrates an instinctive understanding of just how much clients need him, and thus how much they can be persuaded to pay. His charges are carefully spelt out in terms of his own fee, his expenses, his retainers, disbursements, special appointments and bonuses. Wolfe is reluctant to take on the case introduced in Fer-de-Lance, intriguing as it appears, because he cannot identify an obvious invoicee. He becomes more enthusiastic once he hears that the murder victim’s millionaire widow, unhappy that the police have failed to discover her husband’s murderer, has offered a prize of $50,000 to whoever will do so. That’s $3 million by today’s reckoning, so would pay for a lot of time with orchids. Although Fer-de-Lance (‘after the Bushmaster, Archie, the second most poisonous of all the South American vipers’) is the first of the Nero Wolfe mysteries, Archie Goodwin recounts the case as though his reader has been following his tales of Wolfe’s brilliance for years, and the routine at West 35th Street is described on the assumption that it is wholly familiar. The layout of the house, the strict office hours, the lifts, the routine with the plants, Wolfe’s custom-built chair, the red chair that the clients sit in, the arrangement with the front-door buzzer, the fitted carpets everywhere (very unusual in 1934) are all referred to as though we’ve practically stayed there. Although the novels appeared over a period of thirty years they are effectively contemporary. Goodwin presumes familiarity with earlier adventures and with Wolfe’s other hirelings – Saul Panzer, Fred Durkin and Orrie Cather, who carry out Wolfe’s pavement work and provide muscle. Only his nemesis, Inspector L. T. Cramer, doesn’t appear in Fer-de-Lance, although his office is referred to. The fact that Wolfe runs rings round the police is a constant theme, as is his habit of only divulging scraps of information on a ‘need-to-know basis’. Wolfe is a great aphorist: ‘Any spoke will lead an ant to the hub’ or ‘No Archie,’ he says when it is suggested that he borrow money during a temporary income drought, ‘Nature has arranged that when you overcome a given inertia the resulting momentum is proportionate. If I were to begin borrowing money, I would end up by devising means to persuade the Secretary of State to lend me the Gold Reserve.’ Wolfe’s universal expression of contempt is ‘Pfui’. The cases present themselves. Wolfe sifts the evidence and sends Archie hither and thither to interview suspects and look for holes in incomplete narratives. Once Archie has reported back and the mystery begins to unfold, Wolfe calls for the various parties to be questioned and/or summoned. As the evidence accumulates, Wolfe takes stock. In silence Goodwin watches him exercising his formidable brain, sitting behind his desk in his specially engineered chair, eyes closed, fingers interlaced over his chest, lips pursing in and out as he concentrates his marvellous brain on the problem, Goodwin waiting by the telephone for instructions to summon all parties to the dénouement. As a formula it never fails to engage, and the mise-en-scène continues to delight, even though Wolfe’s culinary delights can now be seen in every weekend supplement, and Cattleya laelia, wrapped in cellophane, can be had from London’s Columbia Road flower market at fifteen quid for two.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 44 © Gus Alexander 2014

About the contributor

Gus Alexander runs an architect’s practice in Smithfield. He has squeezed lifts into a hotel or two, and a few hostels, but he’s still waiting to be asked to fit one into a private house.