In 1917, Kathleen Hale arrived in London, fresh out of art school, ‘with only a few shillings in my pocket, my pince-nez delicately chained to one ear and no qualifications whatsoever for earning a living’. Her appalled mother wrote demanding that she return at once to Manchester, and take a shorthand-typing course. Not for the first time, Kathleen refused to obey. ‘I am not going to learn to type. I am going to be an artist. You can send a policeman to fetch me, but I shall come back to London again and again.’ Mother gave up.

If, like me, you are continually aware of your inadequacies when conversing with your clever, fully educated friends, you will, like me, find Kathleen Hale enormously reassuring. She did no homework. She knew no facts. But everyone loved her. In person, as on the page, she was a complete individual: spontaneous, funny, affectionate. Also possessed of enormous artistic gifts, and discipline. Harness those two together, let a handsome father-figure cat pad out of the unconscious and head up the perfect family, put them unblinkingly into any and every adventure, and you have created a classic.

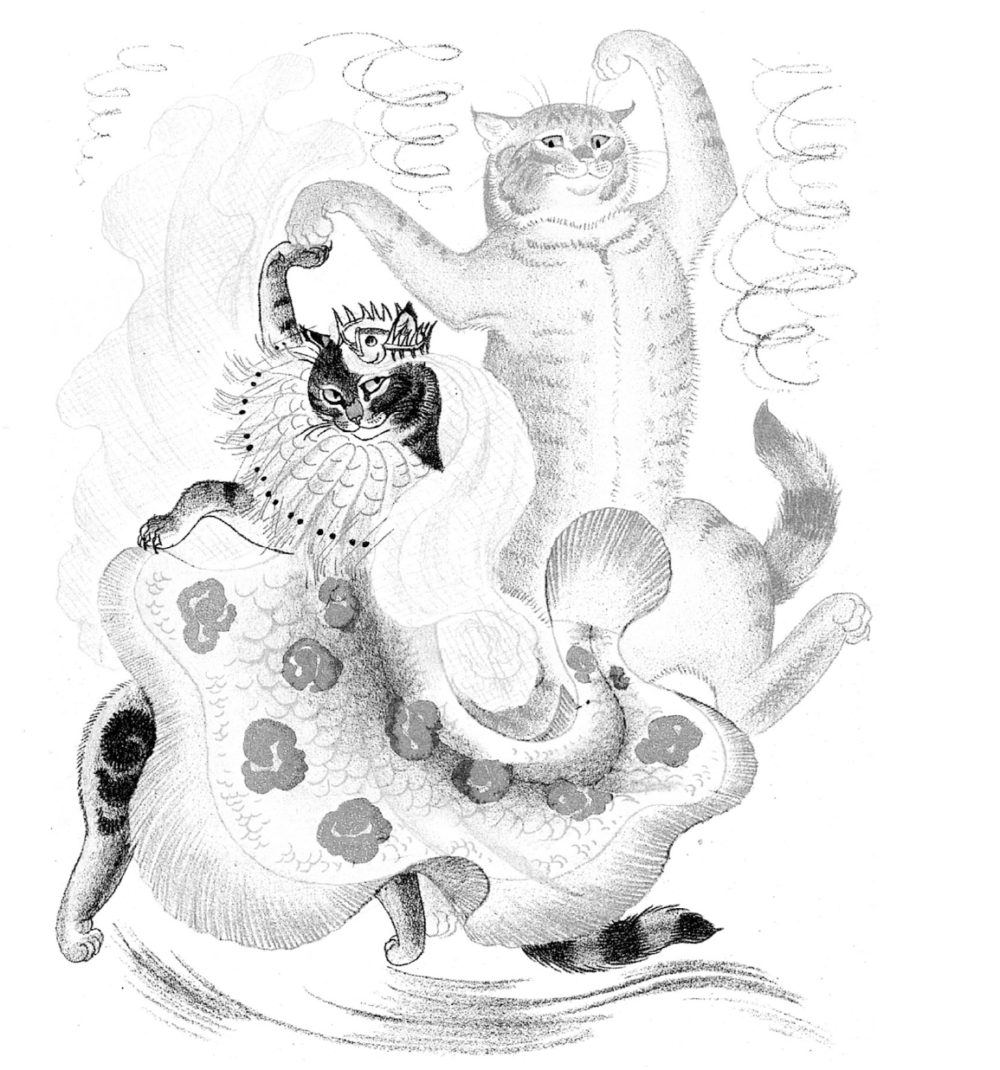

As a child I adored Kathleen Hale’s Orlando books, featuring the adventures of Orlando the Marmalade Cat, his wife Grace and their family, and when my sister-in-law, a bit of a rare book dealer on the quiet, gave me her autobiography as a birthday present last year I was enchanted. Written, like the Orlando books, entirely for the author’s own enjoyment, A Slender Reputation is also, I think, a classic. It contains not a dull line and offers an entirely beguiling portrait of an artist and a century.

Kathleen Hale was born in Manchester in 1898, the third child of a vicar’s daughter and an agent for Chappell Pianos. They were well-off and largely contented, but when Kathleen was five her father died of what was then known as General Paralysis of the Insane, a dreadful consequence of syphilis, fortunately not p

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inIn 1917, Kathleen Hale arrived in London, fresh out of art school, ‘with only a few shillings in my pocket, my pince-nez delicately chained to one ear and no qualifications whatsoever for earning a living’. Her appalled mother wrote demanding that she return at once to Manchester, and take a shorthand-typing course. Not for the first time, Kathleen refused to obey. ‘I am not going to learn to type. I am going to be an artist. You can send a policeman to fetch me, but I shall come back to London again and again.’ Mother gave up.

If, like me, you are continually aware of your inadequacies when conversing with your clever, fully educated friends, you will, like me, find Kathleen Hale enormously reassuring. She did no homework. She knew no facts. But everyone loved her. In person, as on the page, she was a complete individual: spontaneous, funny, affectionate. Also possessed of enormous artistic gifts, and discipline. Harness those two together, let a handsome father-figure cat pad out of the unconscious and head up the perfect family, put them unblinkingly into any and every adventure, and you have created a classic. As a child I adored Kathleen Hale’s Orlando books, featuring the adventures of Orlando the Marmalade Cat, his wife Grace and their family, and when my sister-in-law, a bit of a rare book dealer on the quiet, gave me her autobiography as a birthday present last year I was enchanted. Written, like the Orlando books, entirely for the author’s own enjoyment, A Slender Reputation is also, I think, a classic. It contains not a dull line and offers an entirely beguiling portrait of an artist and a century. Kathleen Hale was born in Manchester in 1898, the third child of a vicar’s daughter and an agent for Chappell Pianos. They were well-off and largely contented, but when Kathleen was five her father died of what was then known as General Paralysis of the Insane, a dreadful consequence of syphilis, fortunately not passed on to his wife or children. Left on her own with three young children and a heap of debts, Ethel Hale sold the house, stored the furniture and – most unconventionally – took up her husband’s business. The children were farmed out to various relatives, and little Kathleen, who had dearly loved her father and was desperately homesick, found herself with a fearsome aunt, who punished her bedwetting by pinning a placard to the back of her dress, reading I WET MY DRAWERS. Her eventual reunion with her mother was not without its difficulties, as may be imagined, especially as older sister Dorothy (like Kathleen, the most beautiful-looking child) was the Paragon, while KH was in no uncertain terms the Rebel. ‘Muvver’, or ‘Muv’, seems to have been a splendid woman, coping with widowhood with a spirit and determination which she certainly passed down to her children. But though Kathleen loved her – ‘the supreme guardian of my life’ – they were often at loggerheads. The child had two passions: drawing, and the keeping of animals (canary, terrier, white rat, little black hen called Blodwen). Nothing else – except the natural world – was of the slightest interest. School – Manchester High – left her cold. Lessons, prefects, best friends, soppy crushes – all a bore. Art class longed for but deadly dull. As for homework: she wouldn’t do it. Ever. Couldn’t see the point. Most of her time at school was spent sitting out in the corridor in disgrace. Fortunately, an enlightened headmistress found a way through all this. She entered Kathleen’s drawings for a scholarship to Reading School of Art, and with this award came the first great turning point in Kathleen’s life. She spent her gap year at Manchester School of Art, found the classes and way of life a revelation, and by the time she graduated from Reading in 1917 and set off for London her vocation was assured. Though her mother couldn’t persuade her to return home, she did alarm her about the perils of the white slave trade, and Kathleen retreated to the safety of the Baker Street YWCA. There, one breakfast time, she met the divinely beautiful Meum Stuart, Epstein’s favourite model, ‘perching there because a period of celibacy was necessary for her divorce’. Meum took Kathleen under her wing. Off she went to Epstein’s tea parties and so – when she was not making a hash of her clerical job at the Ministry of Food – began the happy life she had dreamed of. In wartime London there were two courts of artists: Epstein’s serious lot and Augustus John’s more gregarious drinking crowd. Kathleen decided John’s group was more fun, and after the war, and a period as a Land Girl – driving a magnificent carthorse through town at night, with fruit and veg for Covent Garden – she became John’s secretary. By now, her postwar working life had included designing book jackets for W. H. Smith and, when that dried up, airing a baby in its pram on Hampstead Heath and collecting debts for a window-cleaner. She had worked as a film extra, pawned her inherited gold bracelet and declined to become the mistress of a film magnate. So poor was she when John took her in that she had, through hunger, developed a duodenal ulcer. She could neither type nor do shorthand, but he liked her handwriting. And, presumably, her. But if John’s wife Dorelia had her anxieties about the arrival in the household of this attractive and gifted young woman, they were soon quietened: Kathleen was totally captivated by her. ‘For me she quite outshone Augustus, and was to have more influence on me than anyone I had ever met.’ In the heart of the John household she sorted unpaid bills and unread commissions, scribbled dictation in longhand, squared up canvases, cooked, cleaned and occasionally modelled. ‘We had lots of silly fun, but getting him to start work was always a tussle of wills.’ (She did agree, out of curiosity and helpless laughter, to sleep with him just the once.) But by this time she was caught up in her first great love affair. The artist Frank Potter, whom she met at the Studio Club, was ten years older, fresh from the trenches, and studying at the Slade. ‘He was a true-born Cockney with a rich accent . . . Mother [once again] would have been appalled.’ Potter introduced her to sex (that took a long time) and to the work of the Post-Impressionists, whose bold colours and designs are clearly an influence on the Orlando books. Orlando, however, was still years away: for now, it was all clubs and parties, dancing until dawn and breakfasting on kippers. Potter asked her to marry him, but ‘marriage seemed to me to be something that happened to other people, so I never answered his question.’ They went to France and came back again. They broke up. KH found a little flat in Fitzrovia, glimpsed Sickert, Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell going in and out of studios, and grieved. The man she did marry, in 1926, was, on the face of it, the most improbable choice. At Christmas 1923 she was taken into the London Fever Hospital with a nasty throat infection. The Medical Superintendent was Dr John McClean, who sat on her bed right against the place in her thigh where she’d just had a very painful injection. She burst into tears. This inauspicious beginning led to a strong relationship. Divorced, in his sixties, with three grown-up children, Dr John was ‘infinitely wise and kind . . . a completely three-dimensional character. A great and loving friendship developed between us. I felt I had found my lost father.’ However, Dr John decided that the age gap was too great. Instead, he steered his son Douglas towards her. Two more unlike souls could scarcely be imagined. Douglas McClean was a scientist, rationalist and intermittent depressive; Kathleen Hale an artist, spontaneous and irrepressible, often to be found doubled-up with laughter. On their first night under the same roof (some time before they actually married) Douglas sat contentedly reading the New Statesman, and couldn’t understand what the fuss was about. But in the end, in its own way, it worked. They bought a rundown late Victorian house in Hertfordshire, Rabley Willow, which came with its own cesspit and acres of land. They had two sons, Nicholas and Peregrine (known jointly as the Perriniks) and a nanny called Nonk. Douglas came home from work each day and lost himself in transforming the garden into a beautiful and productive place. Kathleen had a studio. There was a dog. And a marmalade cat. A lot of people came to stay. ‘We built a good life for ourselves and our friends’ – and a marriage more solid than many. In photos, their skinny little boys are beaming with happiness and fun. But Kathleen, having so steadfastly refused to be educated, realized that she would be unable to answer her children’s endless questions. ‘The solution was for them to be able to read as soon as possible . . .’ To this end, she made a marvellous alphabet frieze for their room, and read them the young children’s classics: Beatrix Potter, Babar the Elephant and Ardizzone’s Little Tim books. These exhausted, she made up bedtime stories, starring the marmalade cat. He belonged to Peregrine, and was called Orlando. In 1934, he stepped into his first, Babar-sized, seven-colour picture book, with his first adventure, inspired by a family holiday. Orlando the Marmalade Cat: A Camping Holiday, was published in 1938. ‘One of the reasons that cats are so difficult to draw is that they appear to be boneless, fluid, without any basic structure – round in a round basket, square in a square box, or stretched out like a piece of elastic to twice their normal length.’ Like Beatrix Potter, Kathleen had a great respect for anatomy, and, like Potter, had accumulated a huge number of sketchbooks – ‘of people, objects, animals and nature’ – which became her reference. She found an X-ray of a live cat, which showed the skeleton. ‘I made the illustrations as lifelike as possible.’ But she also, of course, made those cats unlike any others of their time. The modernist influences she had absorbed from the John household, and from the Post-Impressionists, introduced to her by Frank Potter, all stand behind those flattened, stylized shapes, the patterned, rhythmic compositions and quirky views: Orlando’s farmyard, seen from above; a bus-top glimpse of a bowler hat on a pair of human legs; the surreal appearance of a hippo at a kitchen window. ‘I put a few long or unfamiliar words into the stories too, since they make children feel that they have escaped from childhood and are included as equals in the mysterious adult world . . .’ The books, as well as being striking in colour, design and narrative, are also, above all, lovable. Orlando’s blissful marmalade smile, and the tender affection between him and Grace; their ability both to discipline and give fun to their mischievous kittens; to include them in any number of adventures – Orlando becomes a doctor, a judge, buys a farm, buys a cottage (like Babar, he has, through Master, unlimited funds), goes on an evening out, takes to a magic carpet – and bring them safely home again, to fall snugly asleep inside carpet slippers or tiny beds, offer the richest and most appealing picture of family life.My first books were written with a subconscious desire to create for myself the united family that, after the death of my father and the separation from my mother, I had never had . . . Later, as the Second World War progressed, I wrote for the wartime children taken from their families and evacuated . . . I wrote stressing family love, to keep it alive in the children’s minds and to comfort them . . . I based the character of Tinkle the kitten on myself as a child, but emphasised a lovable side to his character to encourage parental understanding . . .Kathleen Hale died in 2000 at the age of 101, having painted until the end of her life. It was her close friend the painter Cedric Morris who once marvelled that she could have ‘hung her slender reputation on the broad shoulders of a eunuch cat’; it was his bisexual partner Lett with whom, on the advice of her psychiatrist, she had a late, therapeutic affair. But that is another story.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 14 © Sue Gee 2007

About the contributor

Sue Gee’s novel, Reading in Bed, was published in 2007. She lives with a splendid cat.