As parents, we hope our children will love the books we ourselves enjoyed, the ones that turned us into readers. But as often as not, our attempts to interest them fail. I remember a friend who was disappointed he couldn’t get his grandchildren to share his love of Swallows and Amazons, a book that had had a huge influence on his life, one that had turned him into a weekend sailor, even encouraged him to build his own boat.

‘What went wrong?’ I asked.

‘They found it impossible to take the book seriously.’

‘Why?’

‘Well,’ – he reddened – ‘because it has a character named Titty. That might pass in the UK, but not here in Canada.’

My own Waterloo came with The Hobbit. Try as I might, I could not get my children interested. My own introduction to Tolkien had come in Mrs White’s grade five/six classroom. At the end of each school day, as a reward for good behaviour, Mrs White would gather her pupils in a semi-circle on the carpet and read to us. This was our favourite part of the day. Over the course of two years, she gradually worked her way through Enid Blyton’s adventure stories but then, toward the end of my final year in primary school, she announced she was going to try something new.

She gathered us together as usual and began to read. It was as if an electric current had gone through the room. We sat up straighter. We pricked up our ears. We had never heard anything like this before: trolls and dwarves, wizards and elves, magic rings and giant spiders, and not told like a fairy story, but written as if it had really happened. We loved it. Each day we rushed through our school work so that we could savour these last fifteen minutes of the school day.

Then the unthinkable happened. We reached the last day of term and she closed the book, unfinished, and wished us all a pleasant summer holiday. I immediately rushed to the public library, took out a copy and finished it. Then I started again, from the beginning.

What was the appeal of The Hobbit? Oh, where to start? There was the dangerous quest for one thing, complete with dragons and a whimsical map. (Maps are important.) There was the gathering of a band of brothers, that common theme of male adventure novels which, when you stop to think about it, is also the appeal of Robin Hood and King Arthur. And then there was the creation of a truly realized fantasy world with its own history, folklore and language.

No one had done this before, at least not on this level. Only later would I realize that Tolkien had borrowed many of his ideas from his study of Old English tales like Beowulf and the Old Norse Eddur. For me personally, a boy who loved fishing and camping, it was Tolkien’s obvious love of the outdoors that appealed. Tolkien loved trees. Think of all the great forests in Middle Earth – Lothlórien, Fangorn, the Old Forest and Mirkwood.

And then there was the journey itself. Even as a child, I think I knew that all the best journeys were made by shanks’s pony, and The Hobbit, with its subtitle, There and Back Again, is, above all, the diary of a long journey undertaken on foot. As a boy, I would lie in bed at night and imagine my own adventures, staff in hand, rucksack on my back, walking through the dark forests of Middle Earth.

In retrospect, however, I think it was the creation of the hobbits themselves that impressed me most. They are likeable heroes – not brave or strong, perhaps even a bit silly, but resilient and resourceful. They are like children, in fact. Hobbits overindulge in the simple things they enjoy most, like eating, drinking, smoking their pipes and singing. Hobbits, I think, embody the kind of virtues Tolkien saw in the average Englishman: kindness, determination, stewardship (so many of his heroes are gardeners) and fidelity, the sort of virtues that were worth fighting for, and which, when challenged, the common man would step up to preserve. For despite many temptations to abandon the quest, in the end the little hobbit Bilbo masters his fear and shows true courage. This is the sort of lesson a child unknowingly absorbs.

But back to my original point: how to interest my children in The Hobbit? Was it even fair to force the novel on them? I decided to take a leaf out of Mrs White’s book. One day, while they were idly drawing or playing with Lego, I opened The Hobbit and began to read aloud, pretending the children weren’t even in the room:

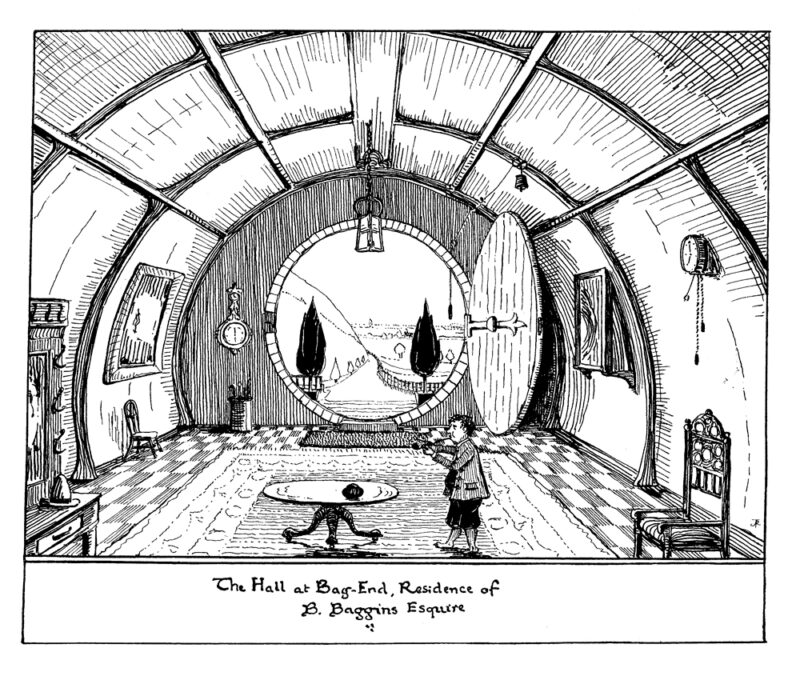

In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit. Not a nasty, dirty, wet hole, filled with the ends of worms and an oozy smell, nor yet a dry, bare, sandy hole with nothing in it to sit down on or to eat: it was a hobbit-hole, and that means comfort.

After the first page or so, my daughter put aside what she was doing and snuggled up next to me on the sofa. The boys were still building weapons of mass destruction, but I noticed their hands weren’t moving quite as quickly. They were pausing from time to time, distracted. After a few more pages, I sighed dramatically and shut the book.

‘What are you doing?’ my daughter said. ‘Don’t stop.’

‘What? You want me to keep going?’

‘Yes,’ they all replied.

‘But I thought you didn’t want to read The Hobbit?’

‘Well, we’ll try a bit more, just to see if it’s any good.’

So all three of them draped themselves on the sofa, and I went on reading. Each night thereafter we carried on until we’d finished the book.

Now this was some years ago, before The Hobbit was turned into a bloated trilogy of films. After seeing them, one of my sons decided to read the book again, this time on his own. I asked him how it compared.

He looked thoughtful. ‘The films missed the point. The Hobbit isn’t an epic, like The Lord of the Rings. It’s a simple story. The movies didn’t need to get so long and complicated. In fact, the best scenes in the movie were taken straight from the book.’

Out of the mouths of babes.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 71 © Ken Haigh 2021

About the contributor

Ken Haigh is a librarian from Canada who misses the days when his children were small enough to curl up in his lap and be read to.