The second half of the seventeenth century in England saw an efflorescence of diaries and memoirs, kinds of writing hardly seen before, but there was a delay of a century and a half before these writings got into print. The Memoirs of the Life of Colonel Hutchinson by his wife Lucy led the field, appearing in 1806, and telling how he held Nottingham Castle for Parliament. Most of John Aubrey’s Brief Lives were first published in 1813, and John Evelyn’s Diary in 1818. This attracted far more attention than the first two and was the stimulus needed to get Pepys’s diary off the shelves of his library which he had left to his old Cambridge college, Magdalene. The Master lent a volume of it to his uncle, the bibliophile Thomas Grenville, who passed it on to his brother William, he who had been Prime Minister at the head of the ‘Ministry of All the Talents’ in 1806–7.

The diary was in some sort of shorthand, unsurprisingly since undergraduates in the seventeenth century were expected to take down lectures verbatim. William Grenville, who had learnt short-hand himself when reading for the Bar, pronounced Pepys’s ‘an excellent accompaniment to Evelyn’s delightful diary’, a transcription was commissioned, and eventually a selection amounting to a quarter of its one and a quarter million words appeared in 1825, with all the gamey passages left out. Fuller and fuller selections followed until four-fifths of the whole, based on a new transcription, appeared in 1875–9. The complete, unexpurgated and brilliantly annotated text edited by Robert Latham and William Matthews was eventually published in nine volumes in 1970–6 (two further volumes, a Companion and an Index, followed in 1983).

In February 1662 Pepys remarke

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inThe second half of the seventeenth century in England saw an efflorescence of diaries and memoirs, kinds of writing hardly seen before, but there was a delay of a century and a half before these writings got into print. The Memoirs of the Life of Colonel Hutchinson by his wife Lucy led the field, appearing in 1806, and telling how he held Nottingham Castle for Parliament. Most of John Aubrey’s Brief Lives were first published in 1813, and John Evelyn’s Diary in 1818. This attracted far more attention than the first two and was the stimulus needed to get Pepys’s diary off the shelves of his library which he had left to his old Cambridge college, Magdalene. The Master lent a volume of it to his uncle, the bibliophile Thomas Grenville, who passed it on to his brother William, he who had been Prime Minister at the head of the ‘Ministry of All the Talents’ in 1806–7.

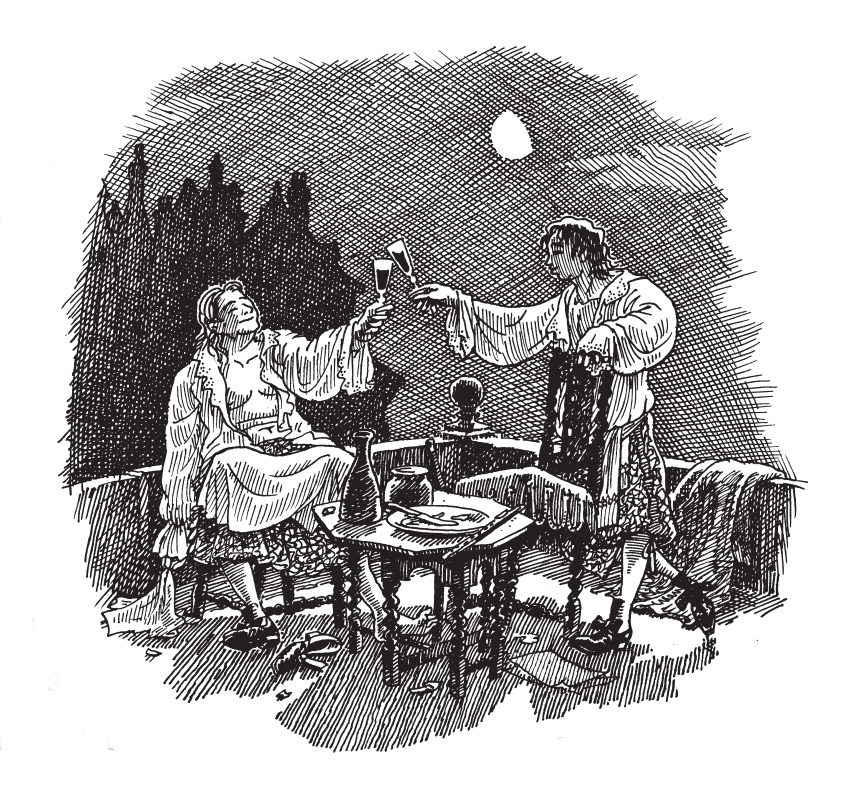

The diary was in some sort of shorthand, unsurprisingly since undergraduates in the seventeenth century were expected to take down lectures verbatim. William Grenville, who had learnt short-hand himself when reading for the Bar, pronounced Pepys’s ‘an excellent accompaniment to Evelyn’s delightful diary’, a transcription was commissioned, and eventually a selection amounting to a quarter of its one and a quarter million words appeared in 1825, with all the gamey passages left out. Fuller and fuller selections followed until four-fifths of the whole, based on a new transcription, appeared in 1875–9. The complete, unexpurgated and brilliantly annotated text edited by Robert Latham and William Matthews was eventually published in nine volumes in 1970–6 (two further volumes, a Companion and an Index, followed in 1983). In February 1662 Pepys remarked, ‘I believe, indeed, our family was never considerable.’ After all, his father was a tailor off Fleet Street and his mother was the sister of a Whitechapel butcher. But other Pepys had done better, one marrying Sir Sidney Montagu, brother of the Earl of Manchester. This connection gave Pepys that vital ingredient for success in the pre-twentieth-century world – ‘interest’. When he left Cambridge in 1654 he became part of the household of his first cousin once removed, Sir Sidney’s son Edward, who had been one of Cromwell’s young East Anglian colonels and was now a member of his Council of State. Soon Montagu was made General-at-Sea, and his long absences gave his steward Pepys the chance to display his administrative abilities. When the diary opens on 1 January 1660, Montagu, under suspicion of being in correspondence with the exiled Charles II, is in disgrace, lying low on his Huntingdonshire estate, while Pepys seems to be going nowhere fast. But soon the game of power-poker that has been played between various contenders since the death of Cromwell in 1658 enters its final phase, and Montagu is reappointed to his old positions. On 6 March he admits to Pepys, ‘he did believe the King would come in’, and he invites him to be his confidential secretary and go to sea with him. By 9 March Pepys has agreed: so begins a career that gives him a ringside seat for the coming decade and sees him the most powerful figure in the Navy by its end. This résumé might make Pepys sound like some smug civil servant, a desiccated mandarin careerist, but the diary shows how far he is from that stereotype. He knows how lucky he is and how much he has to learn on the job: ‘Chance, without merit, brought me in.’ And a note of intimate humanity is established in the first five lines of the first entry, in which he refers to the after-effects of his operation for the removal of a bladder stone – the size of a real tennis ball – in 1658, and his wife’s periods. It is the contrasts and contradictions, the multiplicity of the man’s character revealed there thanks to his consuming interest in, and conscious honesty about, himself, just as much as the history it records, that account for the diary’s appeal. One of the biggest contrasts is between his humanity, vitality and love of life and the pervasiveness of his systematic, bureaucratic, docketing, recording, ordering side. It might be expected that someone who ‘took great pleasure to rule the lines and to have the capital words writ with red ink’, when compiling an index for a collection of contracts, would be a prissy pedant. But Pepys takes just as much pleasure in food (barrels of oysters, dishes of anchovies, neats’ tongues and venison pasties punctuate the entries), plays (he sees 73 performances between January and August 1668), books, interior decoration, clothes, music and beautiful women. He can ‘glut’ himself with gazing on the King’s mistress, Lady Castlemaine – even her fine petticoats hanging in the Whitehall privy garden ‘do me good to look upon them’. In very hot weather in June 1661, ‘I took my flagilette and played upon the leads [flat roof ] in the garden, where Sir William Penn [fellow-member of the Navy Board] came out in his shirt onto his leads and there we stayed talking and singing and drinking great draughts of claret and eating botargo [a pungent fish paste] and bread-and-butter till 12 at night, it being moonshine. And so to bed – near fuddled.’ He can be vain, but his accompanying honesty and self-knowledge win one over. In July 1661 he records how it is ‘a great pleasure to me again – to talk with persons of quality and to be in command’ but then admits to having lied about his inheritance from his uncle, claiming it to be bigger than it was ‘because I would put an esteem upon myself ’. His interest in the small change of life is as unflagging as his curiosity is insatiable, about others, about himself and about the passing scene. In September 1661, when the French and Spanish ambassadors’ entourages fight for precedence in the streets, ‘As I am in all things curious – I run after them with my boy through all the dirt.’ It is thanks to these traits that he records so many of those unconsidered trifles that breathe life into our picture of his day-to-day existence in seventeenth-century London: early rising in summer, often at 4 a.m.; his wife and her maid still doing the monthly wash at 1 a.m.; the need to be lit home by links at night; the prevalence of turkey at Christmas; the regularity with which he ‘takes physique’ to purge himself, and then has to stay at home the following day until the process is complete; the irregularity of working hours; having to be taught the multiplication tables; the time spent walking or going by water or coach to meetings, from the City to Whitehall and vice versa, and the time wasted because the person is not at home or not in his office. One is even grateful to know that, in November 1662, he has ‘some pain in making water having taken cold this morning in staying too long bare-legged to pare my corns’. Pepys has several motives for keeping a diary. It acts as a receptacle for the confessional urge which his puritan upbringing has instilled in him; it is a means of satisfying his aesthetic sense, allowing him to record beauty when encountered and to impose order on experience; it is a response to the scientific imperative to make observations and then induce from them, in his case observations of what Robert Louis Stevenson called his ‘own unequalled self . . . that entrancing ego’; lastly, like the petty cash books, account books, letter books and memorandum books he keeps, it is a part of that ‘setting things in order’ from which he derives so much pleasure. Closely allied to that is his enjoyment at making himself master of a complicated job, able to go ‘to bed with my head full of business, but well contented in mind as ever in my life’. We follow him as he gets to grips with the intricacies of measuring timber and masts; learns the best methods of making sails, or how to tell bad rope hemp from good; enquires about the price of tar and oil ‘and do find great content in it’; and visits Deptford dockyard, ‘looking and informing myself of the stores with great delight’. All this knowledge is the key to stopping corruption and getting the King value for money, vital when the annual peacetime budget for the Navy is £200,000 but the actual cost is closer to £350,000. The fact that Pepys is himself getting backhanders from naval suppliers at the same time does not unduly concern him – it is the custom of the age. As he puts it in March 1664, he is ‘hoping in God that my diligence, as it is really useful for the King, so it will end in profit to myself ’. Certainly by the end of 1665, after the Second Dutch War has begun, his own savings have risen from £1,300 to £4,400. By 1668 they are about double that, and the following year he can afford his own coach. Pepys’s vanity has been mentioned, but this is not the only item on the minus side of the ledger. He is quite unbalanced in his jealousy of Sir William Penn and Sir William Batten of the Navy Board, often imputing the worst motives to them and obviously seeing them as a threat to his own position. He can be foul to his French wife Elizabeth, pulling her nose on one occasion, punching her on another, begrudging her spending on clothes when buying plenty for himself, tearing up his love letters to her. He is consistently unfaithful to her with a range of prostitutes and loose women but in particular with Mrs Bagwell, the wife of a ship’s carpenter whom he can debauch thanks to his official position. The only thing to be said in extenuation is that it is entirely due to his honesty in the diary about this unflattering side of himself that we actually know about it. Rather than dwell on Pepys’s record of his gropings and fumblings, written in a mix of broken Latin, Spanish and French, it is fitter to recall some touches from his great set-pieces. When Charles II comes ashore at Dover in May 1660 Pepys is in a boat close behind, ‘with a dog that the King loved, which shit in the boat, which made us laugh and me think that a king and all that belong to him are but just as others are’. In June 1665 he sees evidence of the Plague for the first time, ‘houses marked with a red cross upon the doors and “Lord have mercy on us” writ there . . . It put me in an ill conception of myself and my smell [a plague symptom], so that I was forced to buy some roll tobacco to smell and chaw – which took away the apprehension.’ During the Great Fire of London he notices ‘the poor pigeons . . . loth to leave their houses . . . till they burned their wings, and fell down’. But of course it is a disservice to pick out plums in this way. Much better to immerse oneself in the diary and enjoy the life of the unforgettable figure who wrote it as much as he so obviously did himself.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 24 © Roger Hudson 2009

About the contributor

Roger Hudson worked for many years at John Murray, the firm that had the chance of publishing Pepys in the 1820s but turned it down. While there, he looked after the Whitbread Prize-winning biography of A. C. Benson by David Newsome, On the Edge of Paradise (1980), some recompense for the earlier error since it was based on Benson’s 5-million-word diary, lodged in the Old Library at Magdalene, Cambridge, where he had been Master.