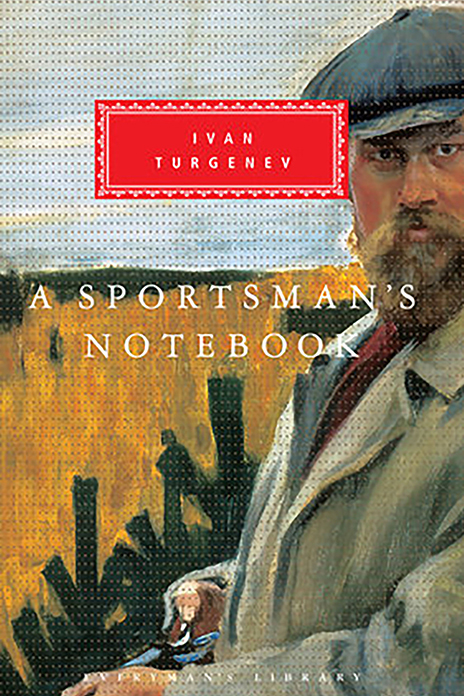

These stories of the 19th-century Russian rural landscape and the difficult life of those who inhabited it were universally popular with the reading public at large and contributed in no small measure to the emancipation of the serfs in 1861.

Waist-high in Kale

Christian Tyler

Tsar Alexander II was warned that Turgenev’s collection of short stories, variously translated into English as Sketches from a Hunter’s Album or A Sportsman’s Notebook, was politically subversive. He read it, nonetheless, and later said it had influenced his decision in 1861 to liberate Russia’s 40 million serfs.

Turgenev’s role as a social reformer is now just an historical footnote. What survives is an extraordinary set of portraits placed in the vividly described landscape of Orel province where he grew up. Posterity should be grateful that he chose to use pen and ink, not soapbox and megaphone, to make his case. He did not even have to argue: he simply wrote down what he heard and saw.

And so today we can still meet the serf Styopushka who is compelled to scavenge for food like an animal, and is encountered on the river bank fixing maggots to the hook of a fellow serf; and the pitiable Lukeria, a beautiful parlour-maid who, though not yet 30, has been reduced to a skeleton by an unidentified illness and lives uncomplainingly in a shed. Then there is Suchok, the ‘master fisherman’, who, when asked why his boat is so leaky, replies ‘because there are no fish in our river’ and who stands shyly before the narrator ‘with head hanging and his hands folded behind his back in the traditional attitude’.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 7, Autumn 2005

Waist-high in Kale

Tsar Alexander II was warned that Turgenev’s collection of short stories, variously translated into English as Sketches from a Hunter’s Album or A Sportsman’s Notebook, was politically...

Read more