I saw the set of books through the window of a second-hand furniture shop in Oxford a couple of years ago. Each with a dark-blue spine stamped with a gilt palm tree, they ran across the top of one of those ‘modern’ sideboards from which Nigel Patrick and Laurence Harvey used to help themselves to drinks in 1950s films. I went in at once and found a complete set of the works of Robert Louis Stevenson, in thirty-five volumes, printed in 1924, bound in soft leather and in superb condition. I bought them for money I couldn’t afford and carried them triumphantly away in a variety of wrinkled carrier bags that the owner pulled out from under his counter.

I’m not going to pretend that I started to read them in order though. I am a huge admirer of Stevenson, but dull Prince Otto comes before Kidnapped and its sequel Catriona, and it was with those two that I started.

I’d first read Kidnapped when I was about 13. It has always been touted as a boys’ adventure story; and until fairly recently Stevenson was dismissed by most critics as surviving only as an author for children. His fellow-writers have seen another figure; for Henry James he was ‘a most gallant spirit and an exquisite literary talent’, and it is not until you read him as an adult that you appreciate the enormous influence that Stevenson had on later writers such as Conrad and Greene, and a whole crew of writers of political and spy novels.

In a sense, Kidnapped, first published in 1886, is the true successor to Treasure Island (1883). The earlier book presents a compelling adventure through the eyes of a boy, Jim Hawkins. But Jim remains a boy, and it is the essential of a true children’s story that the boy or girl remains forever in their childhood world, however thrown into danger they may be for the duration of th

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inI saw the set of books through the window of a second-hand furniture shop in Oxford a couple of years ago. Each with a dark-blue spine stamped with a gilt palm tree, they ran across the top of one of those ‘modern’ sideboards from which Nigel Patrick and Laurence Harvey used to help themselves to drinks in 1950s films. I went in at once and found a complete set of the works of Robert Louis Stevenson, in thirty-five volumes, printed in 1924, bound in soft leather and in superb condition. I bought them for money I couldn’t afford and carried them triumphantly away in a variety of wrinkled carrier bags that the owner pulled out from under his counter.

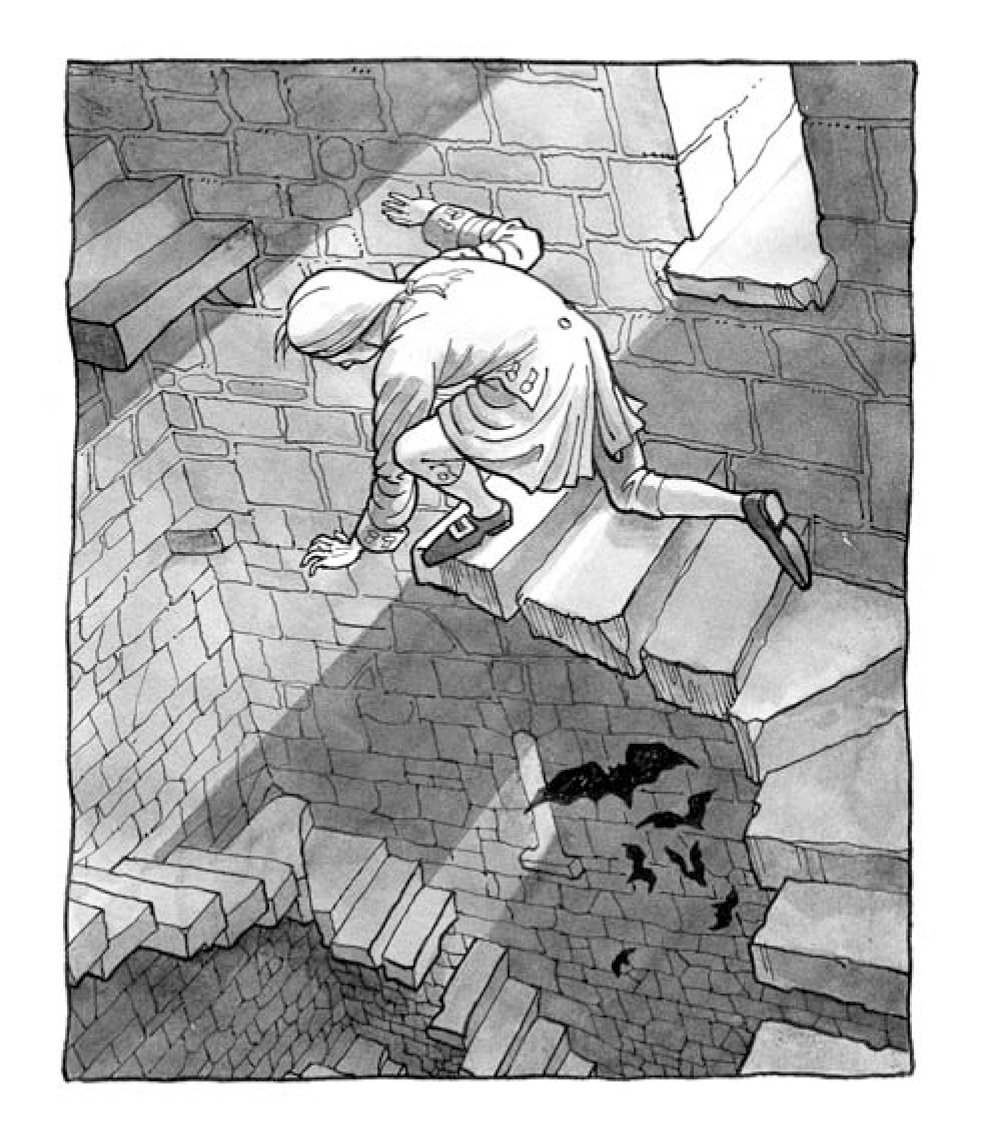

I’m not going to pretend that I started to read them in order though. I am a huge admirer of Stevenson, but dull Prince Otto comes before Kidnapped and its sequel Catriona, and it was with those two that I started. I’d first read Kidnapped when I was about 13. It has always been touted as a boys’ adventure story; and until fairly recently Stevenson was dismissed by most critics as surviving only as an author for children. His fellow-writers have seen another figure; for Henry James he was ‘a most gallant spirit and an exquisite literary talent’, and it is not until you read him as an adult that you appreciate the enormous influence that Stevenson had on later writers such as Conrad and Greene, and a whole crew of writers of political and spy novels. In a sense, Kidnapped, first published in 1886, is the true successor to Treasure Island (1883). The earlier book presents a compelling adventure through the eyes of a boy, Jim Hawkins. But Jim remains a boy, and it is the essential of a true children’s story that the boy or girl remains forever in their childhood world, however thrown into danger they may be for the duration of their stay: the story happens to them, they triumph and then they resume their lives as immortal young heroes. But in Kidnapped, the hero, David Balfour, is already a young man and we see him grow in shrewdness, physical strength and moral fortitude. It is difficult to imagine David being taken in by that charismatic rogue Silver, but then the villains of Kidnapped are grown-up ones: sly, deceitful, treacherous in their lawyers’ offices and government posts. Kidnapped is a novel about the last adventure of boyhood, a novel about being forced to maturity; while Jim inhabits forever the Admiral Benbow inn and Treasure Island, David is forced to come to terms with adult life in the Scotland of the Clearances and near civil war, and the looming future of a new and different Scotland, ruled not by clans but by civil servants. A boy of 17 at the start, sobered by the death of his parents, he prepares to leave his home, provided only with a letter written before his father’s death. It is addressed to his Uncle Ebenezer at the House of Shaws in Cramond, near Edinburgh, and young David sets forth with a high heart to claim his inheritance. And so the story begins. When he comes to the House of Shaws he finds it a near ruin and his uncle a sour old miser and the instrument of the disaster that befalls him . . . But I must stop there. I can hardly believe there is anyone who hasn’t already read Kidnapped, but if you haven’t I mustn’t spoil your pleasure by revealing the plot. Some chapter headings may give a taste of what’s in store: ‘I Run a Great Danger in the House of Shaws’, ‘The Siege of the Round House’, ‘The Loss of the Brig’, ‘The Death of the Red Fox’, ‘The House of Fear’, ‘The Flight in the Heather’, ‘Cluny’s Cage’ and, at last, ‘I Come into My Kingdom’. The book is set in 1751 but there is none of the slow, tedious over-writing of most Victorian historical novels. An unlikely admirer of Stevenson, the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins wrote in a letter that he thought that ‘Stevenson shows more genius in a page than Scott in a volume.’ The writing is as swift and clear as a Highland stream. Indeed, one remembers the great set pieces of Kidnapped as almost filmic. Perhaps that is because of the enormous influence the book has had on the modern thriller: David waking in the hold of a ship at sea, taking him to a life of slavery; the picking up of Alan Breck from a boat in a storm; the alliance of David and Breck when they hold the ship in a terrible fight against the murderous crew. The characters are complex and subtle: Alan Breck is the exact opposite of the Lowlander David; this new friend and rescuer is a Highland gentleman, a Jacobite with a price on his head. Both heroic and preposterous, swordsman and poet, vain and noble, he is a man whose time and place have been taken from him and he is bitter and bewildered. The ship rounds the north of Scotland but is wrecked in a storm. David is separated from Alan and must somehow make his way across the Scottish moors to the east coast. Through David’s eyes we travel across a ruined land. There is something nightmarish in many of his encounters – as a boy I was terrified by the fight between David and a blind man armed with a pistol. And what one sees most clearly when one reads the book as an adult is the picture of a country that is overwhelmingly defeated. The English have at last truly conquered the clans and are in military occupation. The traditions of Highland dress, kilt and claymore have been forbidden. A proud people has fallen into poverty and must go begging. David is reunited with Alan Breck in one of the most dramatic scenes of the book. Breck is a wanted man; he must move east to pick up a ship to join his fellow Jacobites in exile in France. They move by night, lying up by day – once all day on barren rocks at the top of a hill under a mercilessly blazing sun, while the valley below is alive with redcoats hunting Breck. The story of how they reach safety is one of the most exciting adventures described in literature. And this journey, of an ordinary, embattled and innocent young man and his reckless but honourable companion, must surely have inspired the escape of Richard Hannay in Buchan’s The Thirty-Nine Steps, and the hunting of the hero in Geoffrey Household’s Rogue Male, and other nightmarish flights across dangerous landscapes from Tolkien to J. K. Rowling. Well, Stevenson was the first and he is still the best. In 1886, Stevenson was 35 and at the height of his powers. The work he had written immediately before Kidnapped was The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. The duality of human beings is a running theme in his books. In Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde it is the extreme moral and physical division of good and evil in one man; in Kidnapped, the tension between the pragmatism of Scottish and Anglo-Scottish Whigs and the defeated but endlessly rebellious and romantic Jacobites. It is a paradox that haunts David and still haunts Scotland today: it may be difficult to see Alex Salmond as the romantic warrior Alan Breck but the ambition for independence, for separation from the English, is partly inspired by a sense of national humiliation and the lingering resentment that hangs over the memory of those who threw in their lot with the English in the eighteenth century. History has a long reach. Since beginning to write this I have also read Catriona, the novel that continues David Balfour’s story and in which he finds subtler and more ‘civilized’ forms of treachery and deceit in the ‘tall, dark city’ of Edinburgh. Catriona is not really a sequel, more a simple continuation of Kidnapped. As befits the hard-earned maturity of David it is less an adventure and more a story of the conflicts of morality and conduct that affect a young man in a confused and changing world. But the point where David truly grew up was during his flight across the heather and his introduction to both the nobility and the treachery of his fellow creatures. If you have read Kidnapped, as you probably have, do read it again. If you haven’t read it for a long time you will not be disappointed; you will find a deeper and more exciting book than any you remember.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 43 © William Palmer 2014

About the contributor

William Palmer’s latest novel, The Devil Is White, was published last year.