Television in the 1970s and 1980s was educational. Bergerac taught us that Jersey was a seething cauldron of crime; Grange Hill introduced a generation of children to sausages and heroin. And Monkey? Monkey taught us all about the frenzied delights of classical Chinese literature, even if it took some of us a while to realize it.

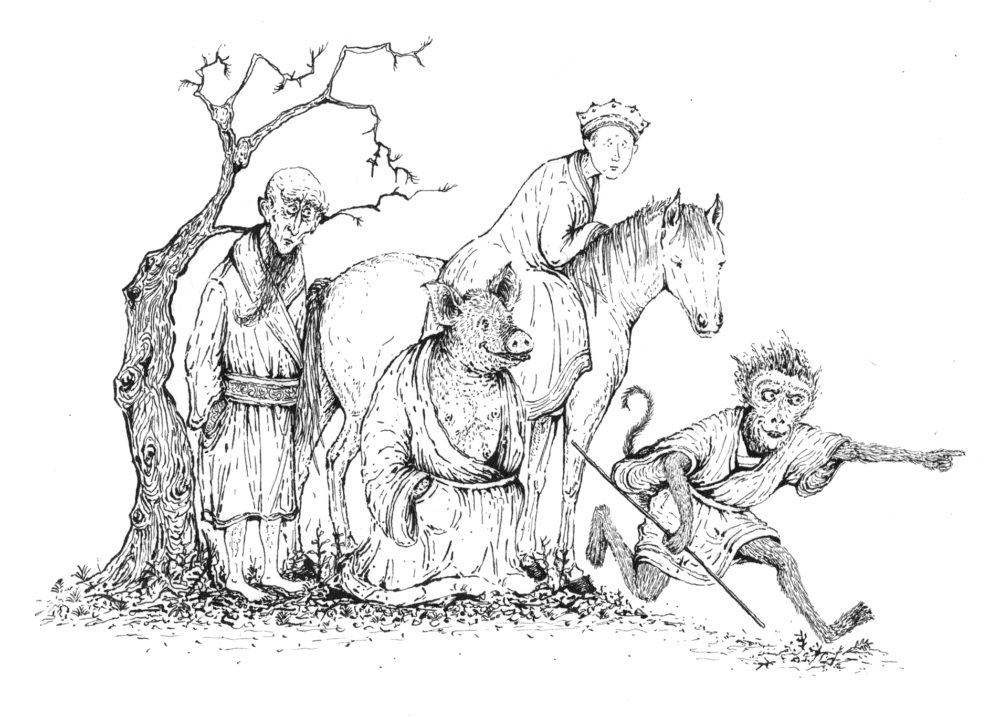

If somehow you missed the brief terrestrial appearance of Monkey, it takes a bit of explaining. The series was a Japanese production, dubbed (presumably deliberately) into comically bad English, and replete with incredibly clunky special effects and fight scenes. It featured a man-monkey who zoomed around a lot on supercharged clouds, a man-pig who was both fantastically greedy and creepily lascivious, a lugubrious man with a skull necklace, who argued with the man-pig, and a woman – or was it a man? – who played a monk who rode on a horse called ‘Horse’. It opened with a weird song and seemed to make absolutely no sense. It was brilliant.

But it wasn’t half as brilliant as the text which inspired it. Journey to the West was written in the latter part of the sixteenth century, at the height of the Ming dynasty, by Wu Ch’êng-ên, a poet, writer and sometime court functionary. It is worth stating at the outset that it is one of the four great classical novels of Chinese literature (along with The Romance of the Three Kingdoms, The Dream of the Red Chamber and All Men Are Brothers). This is something to bear in mind while you’re reading the work too: it’s always reassuring to feel that you’re engaging with one of the Great Works of World Literature when you’re giggling at the manic adventures of the mischievous Monkey king, and humming the theme song of a ’70s martial arts TV show to yourself. Monolithic classics simply aren’t mean

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inTelevision in the 1970s and 1980s was educational. Bergerac taught us that Jersey was a seething cauldron of crime; Grange Hill introduced a generation of children to sausages and heroin. And Monkey? Monkey taught us all about the frenzied delights of classical Chinese literature, even if it took some of us a while to realize it.

If somehow you missed the brief terrestrial appearance of Monkey, it takes a bit of explaining. The series was a Japanese production, dubbed (presumably deliberately) into comically bad English, and replete with incredibly clunky special effects and fight scenes. It featured a man-monkey who zoomed around a lot on supercharged clouds, a man-pig who was both fantastically greedy and creepily lascivious, a lugubrious man with a skull necklace, who argued with the man-pig, and a woman – or was it a man? – who played a monk who rode on a horse called ‘Horse’. It opened with a weird song and seemed to make absolutely no sense. It was brilliant. But it wasn’t half as brilliant as the text which inspired it. Journey to the West was written in the latter part of the sixteenth century, at the height of the Ming dynasty, by Wu Ch’êng-ên, a poet, writer and sometime court functionary. It is worth stating at the outset that it is one of the four great classical novels of Chinese literature (along with The Romance of the Three Kingdoms, The Dream of the Red Chamber and All Men Are Brothers). This is something to bear in mind while you’re reading the work too: it’s always reassuring to feel that you’re engaging with one of the Great Works of World Literature when you’re giggling at the manic adventures of the mischievous Monkey king, and humming the theme song of a ’70s martial arts TV show to yourself. Monolithic classics simply aren’t meant to be this much fun. At its heart, Journey to the West is a pilgrim narrative. Its long opening tells the story of the king of the monkeys, how his curiosity drove him on a path to seek knowledge, near immortality and an impressive selection of superpowers. It recounts how he managed to sneak into heaven by trickery and guile, while cocking a simian snook at the bureaucratic hierarchies of the gods. Eventually cast out for the crime of over-eating the sacrosanct peaches that he was supposed to be tending (a particularly funny episode), and imprisoned beneath a mountain for 500 years, the Monkey king is finally offered absolution by the Bodhisattva. Monkey is charged with escorting the monk Tripitaka to a shrine in India, in order to collect sacred scriptures from the living Buddha, and bring them back for the enlightenment of T’ang China. (Although written in the sixteenth century, the epic is set towards the end of the first millennium.) The remainder of the novel traces the pilgrims’ voyage west, along with three further companions – a dragon transformed into a white horse (who is indeed generally called ‘Horse’, and who never really gets to do very much), the pig demon ‘Pigsy’ (if anything more gluttonous and priapically deranged than his TV equivalent) and the fabulously morbid river demon Sandy. The narrative is episodic, and consequently lends itself perfectly to abridgement, but in each vignette certain themes recur. The travellers are faced with monsters or physical obstacles that challenge their mettle, and they inevitably overcome them in spite of their own personal foibles. Monkey constantly tries to take short cuts or go back on his word and is frustrated in this by the moral presence of Tripitaka (and Horse); Pigsy tries to eat anything he can’t seduce; and Sandy makes wry observations about the futility of life. And there is lots and lots of fighting. In one of the best-known episodes, the pilgrims enter a kingdom dominated by three animal demons who have taken the form of Taoist priests and are persecuting all Buddhists within the region. Tripitaka and his disciples confront the usurpers in a series of elaborate physical and spiritual challenges, intended first to demonstrate the veracity of their own faith in the face of this persecution, and ultimately to reveal the demonic nature of their opponents. Predictably, Monkey’s restless near-omnipotence sees our heroes triumph easily in the first few rounds, but even he is stumped by the prospect of competitive meditation:If it were just a matter of playing football with the firmament, stirring up the ocean, turning back rivers, carrying away mountains, seizing the moon, moving the Pole Star, or shifting a planet, I could manage it easily enough . . . But if it comes to sitting still and meditating, I am bound to come off badly. It’s quite against my nature to sit still. Even if you chained me to the top of an iron pillar, I should start trying to swarm up and down and should never think of sitting still.Eventually, of course, the monk Tripitaka takes on the challenge himself. His own preternatural spiritual powers prove more than adequate, especially when Monkey transforms himself into a caterpillar and crawls up the nose of Tripitaka’s demonic opponent, thereby distracting him and ensuring victory for the pilgrims. Much of the charm of Journey to the West derives from the interrelationship of the four main characters. Monkey is the star, of course, but his gymnastic show-boating is offset perfectly by the frequent attempts of Pigsy and Sandy to get one up on him, or (just as frequently) to get out of the more dangerous scrapes for which he volunteers them. Amid all the zany chaos, the bashing of heads and the epic confrontations, Journey to the West takes place in a precisely ordered world. At times, it seems clear that the author intended his novel to be read as a satire on the complex bureaucracy of contemporary China: Monkey’s initial transgression is caused partly by his inability to comprehend the nuances of divine politesse, and by the failureof the gods to find a place for the self-styled ‘Great Sage Equal of Heaven’ in their own hierarchies. Later, the seemingly straightforward expulsion of demons and dragons from troubled kingdoms is frequently complicated by Tripitaka’s concern to observe appropriate political law. But it is as well to remember that Wu Ch’êng-ên was himself a part of this world, and so were his readers. Fantasy it may have been, but Journey to the West reflected the political and social concerns of the world in which it was composed. This is also a profoundly spiritual story of pilgrimage – although one that is closer in tone to the boisterousness of Chaucer than to the piety of John Bunyan. Monkey, Pigsy, Sandy and Horse all undertake their journeys to atone for past transgressions, and gradually attain enlightenment through the eighty-one challenges that stand in their way. Tripitaka stands apart from the other travellers, but he too overcomes his personal difficulties (and occasional lapses into maudlin self-pity). This is a tremendously entertaining novel, but it’s also a very moving one. The simplest way to access Journey to the West is probably through the abridged Penguin translation by Arthur Waley, entitled simply Monkey. This reproduces the substantial prologue in full, as well as the satisfying conclusion (unlike Chaucer’s pilgrims, Wu Ch’êng-ên’s travellers did finally make it to their destination, and the dénouement is well worth the wait). Crucially, the abridgement also contains several of the most memorable of their adventures in a shade under 350 pages: a reader could read it in the time it would take to fly from Beijing to Northern India today. As the quotations above may suggest, Waley’s translation is light and immensely readable throughout. English versions of the complete text are also available, of which I would especially recommend the four-volume edition of W. J. F. Jenner’s translation published by the Foreign Languages Press in Beijing. Journey to the West is both hilarious and spiritually uplifting; its narrative is exactly the right combination of systematic progress and the repetition of familiar tropes. But it is the characters that stick with the reader. Pigsy and Sandy taunt and tease one another like a bickering couple with divine powers and demonic tastes; Tripitaka and Horse radiate a calm serenity amid the chaos; and the trickster Monkey must be one of the most attractive characters in all of world literature. From his first curious forays into heaven, through violent expulsion to his reluctant conversion to the straight and narrow path, Monkey delights. Perhaps the makers of the TV show had it right after all:

The nature of Monkey is irrepressible!

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 43 © Andrew Merrills 2014

About the contributor

Andrew Merrills normally lives in a world of books in the middle of England, but he occasionally undertakes ambitious pilgrimages for the good of his soul.