One of my favourite books is Wolfgang Kohler’s The Mentality of Apes. I haven’t actually read more than a couple of paragraphs at a time because the contents are of less significance to me than the cover. It is an old paperback with the characteristic turquoise cover that all Pelican books had, and the simplicity of the cover design allows the title to stand out clearly. I take it with me to meetings that I don’t want to go to and place it, obtrusively, on the table, title up.

Another favourite is Krupskaya on Soviet Librarianship which I carry around the library, clasping it to my chest, title outwards, when I’m feeling particularly aggrieved. A useful alternative to The Mentality of Apes but for meetings which threaten to be boring rather than irritating, is The History of Wallpaper, which I like to think is the literary equivalent of watching paint dry.

I realize that this use of books might be seen as reflecting the corny lists that are published every year, usually around the time of the Frankfurt Book Fair, of books with titles so dull or peculiar that it is assumed only extreme nerds would wish to buy them: Extraordinary Rendition: Some Do’s and Don’ts; Oxyacetylene and Its Derivatives; and so on. I don’t find these lists particularly amusing as I cannot see anything much wrong with narrow specialization or expertise, though I know that in the new dawn of inclusiveness they are somewhat unfashionable approaches to life. I suppose I am taking the concept slightly further by trying to locate the right book for the right moment, a title that I can flourish and which will make a statement. And it involves actually acquiring the volumes.

Sadly, the best source of statement books has vanished. The British Library used to run a system called Booknet through which works discarded from public libraries were listed for sale in monthly bulletins. Before the closure of B

Subscribe or sign in to read the full article

The full version of this article is only available to subscribers to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. To continue reading, please sign in or take out a subscription to the quarterly magazine for yourself or as a gift for a fellow booklover. Both gift givers and gift recipients receive access to the full online archive of articles along with many other benefits, such as preferential prices for all books and goods in our online shop and offers from a number of like-minded organizations. Find out more on our subscriptions page.

Subscribe now or Sign inOne of my favourite books is Wolfgang Kohler’s The Mentality of Apes. I haven’t actually read more than a couple of paragraphs at a time because the contents are of less significance to me than the cover. It is an old paperback with the characteristic turquoise cover that all Pelican books had, and the simplicity of the cover design allows the title to stand out clearly. I take it with me to meetings that I don’t want to go to and place it, obtrusively, on the table, title up.

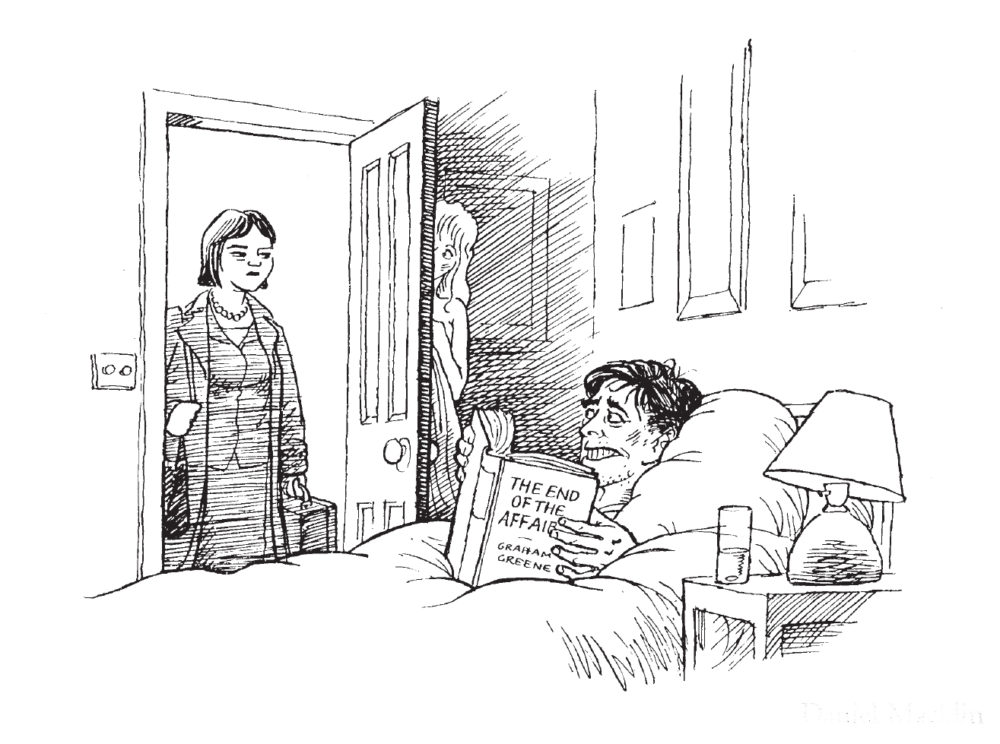

Another favourite is Krupskaya on Soviet Librarianship which I carry around the library, clasping it to my chest, title outwards, when I’m feeling particularly aggrieved. A useful alternative to The Mentality of Apes but for meetings which threaten to be boring rather than irritating, is The History of Wallpaper, which I like to think is the literary equivalent of watching paint dry. I realize that this use of books might be seen as reflecting the corny lists that are published every year, usually around the time of the Frankfurt Book Fair, of books with titles so dull or peculiar that it is assumed only extreme nerds would wish to buy them: Extraordinary Rendition: Some Do’s and Don’ts; Oxyacetylene and Its Derivatives; and so on. I don’t find these lists particularly amusing as I cannot see anything much wrong with narrow specialization or expertise, though I know that in the new dawn of inclusiveness they are somewhat unfashionable approaches to life. I suppose I am taking the concept slightly further by trying to locate the right book for the right moment, a title that I can flourish and which will make a statement. And it involves actually acquiring the volumes. Sadly, the best source of statement books has vanished. The British Library used to run a system called Booknet through which works discarded from public libraries were listed for sale in monthly bulletins. Before the closure of Booknet, the arrival of the lists was a great treat. For a couple of pounds I was able to acquire books I actually wanted, like David Garnett’s autobiographical volumes and an early edition of the Vogue Sewing Book which includes instructions on how to make Chinese knotted buttons. (Chinese buttons mysteriously and maddeningly disappeared from later editions.) I found a fine book, British Weather 1954, to frighten my new American sister-in-law and gave house-room (a good six inches of shelf space) to Motley’s Rise of the Dutch Republic, in homage to S. J. Perelman. Perelman – whom I worship, to borrow his borrowed phrase (from Jonson), ‘this side idolatry’ – lashed himself ‘to the brink of nervous collapse reading the same sentence over and over again in Motley’s Rise of the Dutch Republic, desperately trying to ignore Mrs Fuscher as she stood silhouetted against the sun in a diaphanous sports dress’. Another useful acquisition was Martineau’s Types of Ethical Theory, which I’d always thought P. G. Wodehouse had invented. In Joy in the Morning, Florence Craye, ‘seeming to look on Bertram Wooster as a mere chunk of plasticine in the hands of the sculptor’, sought to mould him by throwing out Blood on the Banisters (which Wodehouse did invent, I have checked) ‘and substituting for it a thing called Types of Ethical Theory. Have you ever dipped into Types of Ethical Theory? The volume is still on my shelves. Let us open it and see what it has to offer . . .’ This was a useful Christmas present for the spouse-equivalent who has everything. I also have a small collection of potential stocking-fillers, viz.: Harold Blount’s provocative Pigeon Racing My Way, Acheson on Modern Goose-keeping and Birtwhistle’s Duck-keeping for Profit and Pleasure. It is not necessary to search out obscure titles to make a point. On long air trips, particularly on my least favourite national carrier, I like to lie back in martyrdom with an open copy (title up) of Apsley Cherry-Gerrard’s The Worst Journey in the World covering my face. A useful alternative is Nadezhda Mandelstam’s Hope Abandoned. Once you get the idea there is no stopping. Apart from using them as door-stops, for propping up shelves and wobbly beds and as reading matter, here is a whole new side of books to be exploited.Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 20 © Frances Wood 2008

About the contributor

Frances Wood works in the British Library. She has written several books but purchased many thousands for a variety of reasons, not all of them particularly rational.