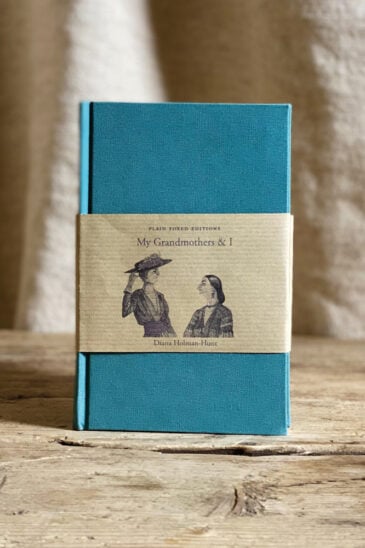

My Grandmothers & I (Plain Foxed Edition)

Diana Holman-HuntSubscriber discount

In stock

[. . .]

‘Ah, good morning my pet,’ said Grand, rubbing her eyes, and gulping at something that made her face fatter. ‘I hope you slept soundly?’

‘The sofa’s like a canoe, a canoe made of iron.’

‘We’d better say our prayers,’ she said. ‘Prayers in the morning? I never say prayers in the morning, nobody does.’

She knelt on a stool, facing the wall on the right of her bed.

‘Dear me, what a heathen.’ She gazed at the shelf, on which stood a vase of plaited palm crosses and a framed drawing of hands, lifted in prayer.

‘This is Dürer’s famous drawing, only a reproduction of course. D’you know,’ she asked, turning round, ‘Mr Ruskin said that, in his opinion, Holman was the best draughtsman since Dürer? And,’ she pointed to a glass case over the shelf, ‘this is Holman’s Order of Merit and, in that frame, are his palette and brushes.’ She closed her eyes and her lips seemed to gibber. She had told me all this before.

‘I was thinking,’ she said, getting up, ‘what a pleasant surprise it would be for your grandmother, if while you were here, you learnt the Lord’s prayer in French or even Italian.’

Fowler wouldn’t like it. She would call it tommyrot.

‘You’ve outgrown that childish prayer you said to me last night. Really you should put your father first, not last after the pugs and Mrs Hopkins, whoever she may be. I expect Arthur is the Pritchard boy? I noticed he came early on the list and I must confess, I was rather hurt not to hear my name.’

‘Oh dear, I didn’t think . . .’

‘Notre Père qui est en ciel,’ she murmured, ‘it distresses me, your religious education is not, well not exactly . . . Ah, I hear Helen with our breakfast.’

The egg wore a red flannel cap: I attacked its shell with gusto, hammering ‘Foreign’ into splintered letters. When I dug my spoon in the top, I drew back in disgust: ‘It smells!’

‘But it smells bad,’ I explained, ‘like . . .’

She picked it up and sniffed: ‘It’s not new-laid but it’s fresh and perfectly wholesome. It might have been more prudent of Helen to fry it. I should use plenty of salt and pepper.’ She set the egg back in its cup and walked round the room, sipping her tea.

‘Now what delightful thing shall we choose to do today?’ She surveyed the invitation cards stuck in the looking-glass frame, letting some more flop in the fender.

‘The Arthur Somervilles are at home tomorrow – you must take your music, I haven’t heard your new piece – also the dear Israel Gollanczs. We must try and do both. No end of people have asked us to tea, Lilian Bayliss, she’s so gifted! George Henschell . . . even Mr Russell Flint. Here’s a note from Annie Swynnerton. She says: “be sure to bring Diana”, and we must remember to call on your Aunt Mary Millais. She is Jack Millais’ daughter you know, and sat in your family pew, as a child, for his popular pictures: My First and Second Sermon.’

‘I sit in that corner now,’ I said.

Aunt Mary lived in Argyle Road and could be relied upon to produce buns and cherry jam. Once she had meringues, left over from the day before when her nephew Raoul had been to tea. She covered her furniture with sheets and we sat amongst a lot of shapes that might be people listening. Her nose was red, and she complained: ‘Although your grandfather called my father Johnnie, you should call him uncle Jack, or Great uncle Jack would be better. Remember he was Sir John Everett Millais.’

Grand always broke in: ‘Without meaning to sound offensive, Mary, how typical it was that your father rejoiced in an ostentatious title; whereas my ever-modest Holman preferred the more subtle and distinguished honour of the Order of Merit – a privilege to which few . . .’

‘We’ve an invitation for Thursday,’ said Grand, interrupting my thoughts, ‘from Lord Leverhulme to see his pictures.’

To me he looked like an apple . . . What could I do with my egg? Would Helen give me away if I poured my hot milk into the tea-pot?

‘Why, I do believe we’re free this afternoon. You choose, my pet, we’ll do exactly as you like.’

‘I should like to go to Selfridges,’ I said, without hesitation.

‘Selfridges? Who, where and what are Selfridges?’ ‘It’s a wonderful place,’ I said, feeling excited. ‘Fowler took me there one day to have an ice and you’ve no idea how interesting it is, and, and . . .’ I faltered, seeing her face stiff with disapproval, ‘what lovely things they have.’ I patted Edward.

‘A shop! I scarcely think – no, no. I would suggest the Zoological Gardens, if we must indulge plebeian tastes. Your father is a Fellow, indeed he has presented some exhibits so we should be admitted free of charge.’

‘I’d rather go to the Serpentine and feed the ducks, if Helen has some crumbs.’

‘I’ll tell you what,’ she exclaimed, as if she’d had a sudden inspiration, ‘we will go to the National Gallery or the Tate; and then, if we feel inclined, we’ll pay a call. Now there’s no time to dawdle, when you’re dressed and we’ve made the bed you can run downstairs to Helen. I’m sure she would appreciate a little help. Later I thought you could put on a pinafore and sweep up the leaves in the garden. Would that appeal to you at all?’

‘Yes, that would be nice,’ I said, leaning out of the window and throwing my egg at the elm, which had a notice chained to its trunk: ‘William Makepeace Thackeray and his children played round this tree.

[. . .]

Waiting for breakfast on Friday morning, Grand studied the invitations round the looking-glass over the fireplace. ‘So today has come at last, with Anstey Guthrie’s party. He’s such a generous dear. You’ve read his stories? Fallen Idol, Vice Versa, The Brass Bottle, I can’t remember all the titles. His delightful nephew Eric always helps him entertain.’ She turned round; her eyes were shining. ‘I’ve kept my surprise until now, a surprise for you, my pet.’

My hopes rose. Could it be a kipper?

She went to a drawer and pulled out something that looked like a choir boy’s surplice. Helen came in with the tray. The egg had been fried.

‘Diana’s classical dress,’ cried Grand, ‘it’s fit for a Goddess!’ She shook out the stuff and displayed it over the sofa. The egg on the tray was congealing. ‘The hours, the golden hours I’ve spent on the embroidery! I know I shouldn’t boast, dear Holman was so admirably modest, but look at the crescent moon, Diana’s symbol, made of silver beads! They were so fine I couldn’t thread them on a needle. I used my own hair and a magnifying glass, stitching under the lamp, night after night, longing for your visit. As I worked I recalled the charming brown wedding dress Holman designed for pretty Ellen Terry when she married Mr Watts and I remembered the exquisite embroidery he worked on the sleeves of – was it Orlando’s blouse? No, he wore the armour which was lent by Mr Frith. The maid said, “There’s a tin weskit and trousers in the hall . . .”’

‘You used your own hair?’ I interrupted and stared at her in wonder.

‘And look at the sprigs of daphne which I worked into a border round the hem. Two yards at least. I copied the design from a book in the British Museum – Montagu House as Holman always called it. The other day I caught the custodian reading the Weekly Herald. I reported him of course; he was clearly a scoundrel . . .’

It dawned on me slowly that I was to wear this horrible garment at the party. ‘But I have a nice dress. It isn’t unpacked. Red velvet, and Fowler says the collar is Brussels lace – it’s in points like this.’ I traced a zig-zag on the table. ‘I’ve got a white fur coat with cord frogging – the lining is satin – and black kid shoes with silver buckles and white silk socks. Everything’s there in my hamper. Helen, I mean someone, should have steamed the velvet; Fowler gets so cross if anything is creased.’

‘But of course you must wear this dress and be a little Goddess. Hop out of bed and let me hold it against you.’

It had no shape and hung in limp folds from my shoulders to the ground. It looked like a curtain.

‘Please Grand,’ I pleaded, ‘don’t make me wear it!’ ‘My dear child!’ She dived back to the drawer and pulled out coils of silver ribbon. ‘To make it becoming we bind the classical folds to your body, and your curls . . .’ She swept up my hair in her hands and drew me to the glass. I looked like a poor skinned rabbit. ‘Your curls must be dressed like this’ – she picked up a silver brush, and stuck some hairpins in her mouth, ‘bound here and there, and tied high at the back in a tuft of ringlets.’

‘No, no, I don’t want to be a Goddess!’ The dress had fallen on the floor. I ruffled my hair and I stamped in temper on the beads.

‘Youth is cruel,’ she whispered sadly, picking up the dress and sinking on the sofa. We sat panting and staring at each other. Her eyes were wet with disappointment, and I felt defeated. Tears rolled slowly down her face. ‘It’s all right, Grand,’ I seized her skinny wrist, ‘don’t you worry, I’ll wear it.’ I would wear it as a sacrifice for burning my harness and lying. After all it wasn’t asking much; I might have had to drown a kitten.

Extract from My Grandmothers and I, Chapter 2 © The Estate of Diana Holman-Hunt, 1960

Sign up for dispatches about new issues, books and podcast episodes, highlights from the archive, events, special offers and giveaways.

By signing up for our free email newsletter or our free printed catalogues, you will not automatically be subscribed to the quarterly magazine. To become a subscriber to Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly Magazine, please visit our subscriptions page.

Slightly Foxed undertakes to keep your personal information confidential. You can read more about this in our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe from our list at any point by changing your preferences, or contacting us directly. Alternatively, if you have an account you can manage your preferences in your account settings.

Sign up for dispatches about new issues, books and podcast episodes, highlights from the archive, events, special offers and giveaways.

What delicious and telling dialogue. Although I was born and grew up in South Africa and my grandmothers were not well connected, they too had eccentricities and attachments which are the stuff of family mythology.