Blue Remembered Hills (Plain Foxed Edition)

Rosemary SutcliffSubscriber discount

Not in stock

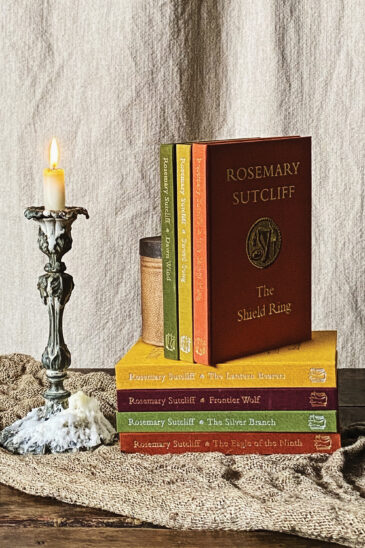

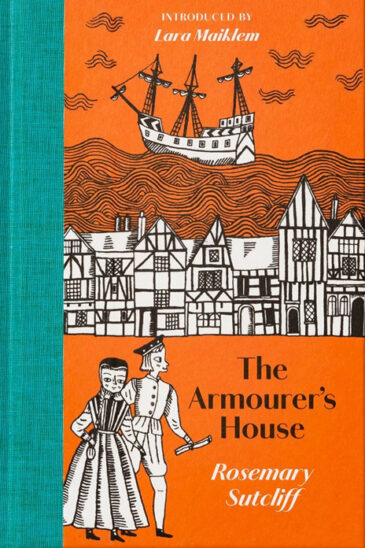

Rosemary Sutcliff was the creator of some of those worlds, and years after I first encountered her through her early books The Eagle of the Ninth and The Armourer’s House, I came to know her again – insofar as one can know such a complex person – through her memoir Blue Remembered Hills. It was first published in 1983 and the cover shows its author sitting in a wheelchair in a garden, looking straight out. It is in some ways a startling picture for a book jacket, for her body, hands and arms are twisted by the juvenile arthritis, known as Still’s Disease, that burned its way through her as a child, leaving her permanently disabled. But what to me is most arresting about the photograph is her direct and humorous gaze. It sums up the spirit of Blue Remembered Hills which, despite the inevitable pain it often records, is the very opposite of a misery memoir. It is a record of the growing up and making of a writer, and it is full of poetry, humour, affection, joy in people and the natural world, and the kind of deep understanding that can come out of some very hard experiences. It is a book I would recommend to any apprentice writer as an example of what really good writing is.

Rosemary Sutcliff was born in 1920, the only child of a naval father – a dear, straightforward man who ‘you could never for a moment have mistaken for anything but a sailor. He had a quiet steady face with a cleft chin, and grey-blue eyes crinkled up by years of narrowing them against rain and wind’ – and a pretty, manicdepressive mother with bags of charm and a wild imagination, who in an ideal world would probably have become an actress but instead found herself travelling from naval station to naval station – Malta, Chatham, Sheerness. And although she loved dancing and parties, she missed out on the social life that went with being a naval wife because she was caring for a sick and increasingly disabled child.

‘She was wonderful, no mother could have been more wonderful,’ writes Rosemary. ‘But ever after, she demanded that I should not forget it nor cease to be grateful, nor hold an opinion different from her own, nor even, as I grew older, feel the need for any companionship but hers.’ It was an intensely close and intensely difficult relationship – but as Rosemary observes: ‘Very few of the worthwhile things in this world are all that easy.’

Even so, in some ways Rosemary’s was an enchanted childhood, lived among the vivid sights and sounds of the dockyards, ‘the smell of pitch and hot metal, wood and white paint, salt water and rope and oily smoke’, which would later feed into her books. There were the people, too, of these small closed communities – adults on whom Rosemary, as an only child who couldn’t walk very well, was particularly dependent, though she did make friends of her own.

Memorable among these was Miss Beck, who ran a school in Chatham for the children of naval families, with ‘no teaching qualifications whatsoever, save the qualifications of long experience and

love’. ‘Any elementary schoolteacher of today would have fallen into strong hysterics or sat down with a banner in some public place after one look at our schoolroom, though I don’t think we ever had much fault to find with it,’ Rosemary writes. ‘It had mud-coloured walls with damp stains in the outer corners, three shelves of limp and weary school-books, a bit of unravelled carpet on the floor.’

In this unpromising setting Miss Beck’s students made cross-stitch kettle holders, drew elaborate kaleidoscopic patterns on graph paper and learned to read from a tattered copy of Grimm’s Fairy Tales. When Rosemary joined Miss Beck’s Academy at the age of 7 or 8 she was still unable to read, but by the end of her first term, ‘without any apparent transition period’, she was reading anything that came her way. A lesson there perhaps? Certainly the description of the relaxed and happy days given over to singing around Miss Beck’s piano, declaiming verses from Macaulay’s Lays of Ancient Rome, and observing what Miss Beck called ‘the Beauties of Nature’ make one think rather sadly of the world of SATs and League Tables in which children live today.

Sometimes Rosemary’s father was away on foreign postings, and then she and her mother were relegated to digs in places like Westgate, on the bleak north Kentish coast, or to the mercies of

Uncle Acton, the good-hearted bad penny of the family, who had spent a brief working life building roads in India, was fat, funny and fond of the bottle, and given to renderings of the ‘Waikiki War

Chant’ and ‘Bye Bye Blackbird’ on the Hawaiian guitar.

Interspersed with these were Rosemary’s frequent stays in hospital. They were lonely, often painful experiences, but even at this early stage in her life Rosemary could observe and admire the skill of her surgeon, kindly Mr Openshaw, who could cut off a plaster cast from hip to toe in one unceasing movement without leaving a single mark on her body. And of Mr Snow the instrument maker, much loved by the children, who would go to any lengths to make sure that his small patients were comfortable when he fitted them with callipers and splints.

It was after one of these stays that Uncle Acton had the inspiration of installing Rosemary, her mother and Uncle Acton’s long-time companion Miss Edes (Uncle Acton was not the marrying kind) for a six-week break in a bungalow called La Delicia on Headley Down, near Haslemere. Despite the frequent recurrence of what Uncle Acton called his ‘malaria’, which made him strangely unsteady on his feet, it was a magical time, ‘filled with the smell of leaf-mould and pine woods and bonfire smoke and frost; and above all of lamp smitch . . . to me one of those magical smells which open doorways in the mind, letting out the sights and sounds and smells of some other place and time’.

There were other magical times too – especially those when she and her father sat down together to look at the albums of his travels, their brown hessian covers ‘folded back with a heart-leap of

expectancy’ to reveal fading photographs – of ships and ‘grinning faces in balaclava helmets, with icebergs in the background . . . Pompeii, with the wheel ruts of chariots deeply shadowed by the

afternoon sun on a paved street . . . the Lyon Gate at Mycenae in the days when you could pick up shards of Mycenaean pottery as easily as anemones from the rough grass’. The writer in her was storing it all up, just as she was storing up the feel of the marsh country round Sheerness, and of the South Downs, where the family sometimes went to visit her grim Aunt Lucy.

When her father retired from the sea the family moved to Torrington in North Devon, where her father had been born and bred and where they had always taken their holidays. They bought a

house called Netherne, perched on its own on high ground on the edge of Dartmoor, and – country people at heart as they had always been – it felt like heaven. They had hens, and vegetables, and an Airedale puppy called Mike, and her father wrote Sailing Directions for the Admiralty in ‘a sort of cabin’ in the garden (a perpetual job as they almost immediately went out of date). Rosemary loved her small bedroom with a view of the crown of a big lilac tree on one side and ‘Orion hanging in at the Dartmoor window’ on the other. She loved the sounds of the curlews coming in from the coast, the owls that ‘perched on the chimney to warm their feet, and made eerie noises down to us’, and the magical moment of cockcrow in the first green light of morning, ‘a sound with a bloom on it, like dew, and shaped like a fleur-de-lys’.

The nearby school, however, was not a success. Rosemary left at 14 and went to Bideford Art School, where she was the baby of the class, treated kindly by the other students, but definitely not part of their social world – though in time she became extremely skilled as a miniaturist, whose work would even one day cause a stir at the Royal Academy.

Deep loneliness was beginning to set in, her mother was becoming increasingly depressed and difficult to live with, and neither of her parents could see that Rosemary, at 16 and 17, was in desperate need of company of her own age. So of course she fell in love with any young man who paid her the slightest attention – first with her cousin Edward, a bittersweet experience that ended with the declaration of war in 1939, when Edward, who was in the Navy, went off to join his ship.

Her father went off too, to command his own ship, and Rosemary and her mother were left alone to soldier on at Netherne in increasing isolation. And then, after the war was over, in the summer before the great freeze of 1947, along came Rupert, the son of a recently arrived neighbour, invalided out of the RAF, glamorous with darkly flaming red hair and ‘blazingly-golden hazel eyes’, who spoke to her as an equal – ‘the first person to whom it ever occurred that I could be asked out without my parents’. They grew closer and closer, but then Rupert clearly took fright, and eventually had to tell her that he had fallen in love with someone else. He broke her heart, and I felt my own heart breaking at the description of their last bleak parting: ‘Why does it seem so much more final when somebody goes away in a train than when they drive off in a car?’

Fortunately for us, however, she had just begun to discover writing and before long her first book for children, The Queen Elizabeth Story – ‘written out of heartache, but also out of something

set free within myself ’ by that searing experience – was accepted by the Oxford University Press. There she ends her story and the rest, you might truly say, is history. It is a wonderful memoir, and one feels braver somehow, more alive, more philosophical for reading it. Because it is written out of the truth of the heart, it is timeless – the kind of book one can return to and find the same golden qualities again and again.

Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 17 © Hazel Wood 2008

Sign up for dispatches about new issues, books and podcast episodes, highlights from the archive, events, special offers and giveaways.