Country Life Book of the Week

‘The most brilliant, hilarious book’ India Knight

‘Probably my book of the year’ Rupert Christiansen

‘When I asked a group of girls who had been at Hatherop Castle in the 1960s whether the school had had a lab in those days they gave me a blank look. “A laboratory?” I expanded, hoping to jog their memories. “Oh that kind of lab!” one of them said. “I thought you meant a Labrador.”’

As we discover from Ysenda Maxtone Graham’s quietly hilarious history of life in British girls’ boarding-schools between 1939 and 1979, this was a not untypical reaction. Today it’s hard to grasp the casual carelessness and even hostility with which the middle and upper classes once approached the schooling of their daughters. Education, far from being regarded as something that would set a girl up for life, was seen as a handicap which could render her too unattractive for marriage, and with some notable exceptions such as Cheltenham, girls’ boarding-schools went along with the idea. While their brothers at Eton and Harrow were writing Latin verse and doing quadratic equations, girls were being allowed to give up any subject they found too difficult and were instead learning how to lay the table for lunch.

Fathers tended to choose girls’ boarding-schools for arbitrary and often frankly frivolous reasons. Hatherop, for example, was popular with some because of its proximity to Cheltenham Racecourse. One girl’s parents chose Heathfield ‘because none of the girls had spots’. Not surprising perhaps that many of them left school without a single O-level.

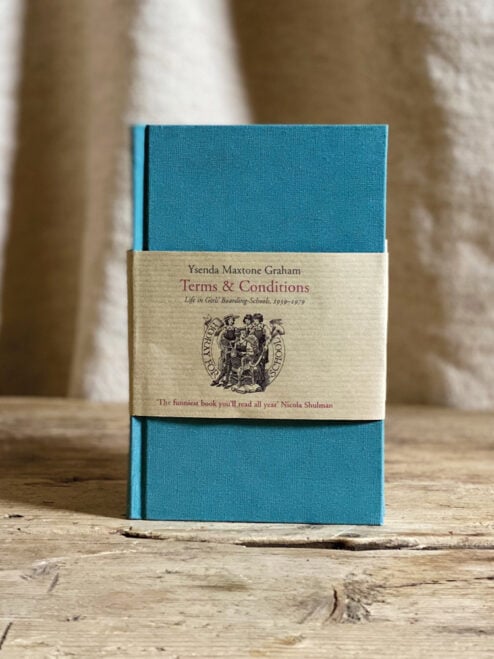

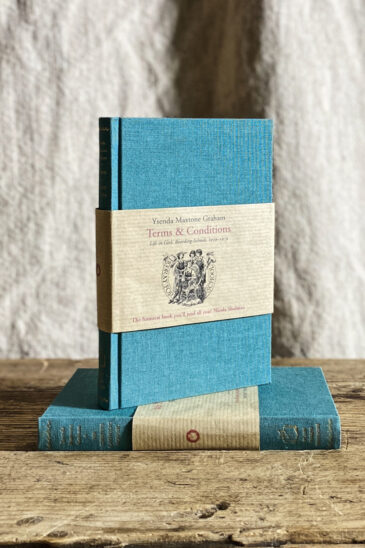

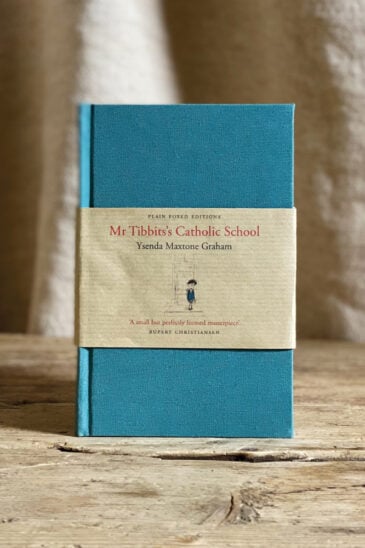

Harsh matrons, freezing dormitories and appalling food predominated, but at some schools you could take your pony with you and occasionally these eccentric establishments – closed now or reformed – imbued in their pupils a lifetime love of the arts and a real thirst for self-education. In Terms & Conditions Ysenda speaks to members of a lost tribe – the Boarding-school Women, grandmothers now and the backbone of the nation, who look back on their experiences with a mixture of horror and humour. If you enjoyed Mr Tibbits’s Catholic School you’ll certainly enjoy this.

A number of famous women were interviewed for this book (among them Arabella Boxer, Amanda Craig, Josceline Dimbleby, Valerie Grove, Fiona MacCarthy, Emma Tennant, Ann Leslie, Artemis Cooper, Katherine Whitehorn, Polly Toynbee, Judith Kerr and Anne Heseltine*) but famous or not, all are equally important to the story.

‘This is not a history of women’s boarding schools. It’s not easy to say where, exactly, you would shelve it. It could be under memoir. Or is it more like anthropology? . . . The other option would be comedy, as it’s the funniest book you’ll read all year.’ – Nicola Shulman

Acknowledgments

Jane Addis

Pippa Allen

Anne Barnes

Susan Beazley

Phoebe Berens

Patricia Bergqvist

Caroline Bingham

Lady Arabella Boxer

Josephine Boyle

Charlotte Bradley-Hanford

Fiona Breeze

Fiona Buchanan

Erica Burgon

Morag Bushell

Elizabeth Butler-Sloss

Josie Cameron Ashcroft

Sue Cameron

Sarah Canning

Aurea Carter

Rosemary Chambers

Gillian Charlton Meyrick

Jane Claydon

Virginia Coates

Cynthia Colman

Artemis Cooper

Diana Copisarow

Camilla Cottrell

Rosie de Courcy

Amanda Craig

Caroline Cranbrook

Linda Cubitt

Anna Dalrymple

Gillian Darley

Patricia Daunt

Mary Davidson

Caroline Dawnay

Bolla Denehy

Mary-Ann Denham

Josceline Dimbleby

Sarah Douglas-Pennant

Pat Doyne-Ditmas

Sally-Anne Duke

Sally Echlin

Margaret Ellis

Judy England

Alexandra Etherington

Julia Fawcett

Maggie Fergusson

Charlotte Figg

Serena Fokschaner

Liz Forgan

Sheila Fowler-Watt

Catherine Freeman

Camilla Geffen

Phyllida Gili

Jane Goddard

Amanda Graham

Anne Griffiths

Valerie Grove

Griselda Halling

Anna Hamer

Rosemary Hamilton

Georgina Hammick

Anne Hancock

Tanya Harrod

Selina Hastings

Louisa Hawker

Anne Heseltine

Lisa Hiley

Clare Hill

Helen Holland

Bridget Howard

Mary James

Sheila Jenkyns

Marigold Johnson

Rachel Kelly

Vanessa Kent

Barbara Kenyon

Judith Keppel

Judith Kerr

Jackie Kingsley

Georgina Lawless

Ann Leslie

Patricia Lombe-Taylor

Jane Longrigg

Laura Lonsdale

Fiona MacCarthy

Jennifer McGrandle

Angela Mackenzie

Georgina Macpherson

Sharon McVeigh

Victoria Mather

Claudia Maxtone Graham

Robert Maxtone Graham

Mary Miers

Lizie de la Morinière

Juliet Mount Charles

Lucinda Mowbray

Cecilia Neal

Sophie Neal

Penny Neary

Georgina Norfolk

Clarissa Palmer

Victoria Peterkin

Henrietta Petit

Georgina Petty

Carole-Anne Phillips

Daphne Rae

Margaret Redfern

Michaela Reid

Gigi Richardson

Sal Rivière

Caroline Robertson

Markie Robson-Scott

Sophia Ruck

Rowena Saunders

Cicely Scott

Barbara Service

Hew Service

Rita Skinner

Gabrielle Speaight

Rosie Stancer

Morar Stirling

Cicely Taylor

Emma Tennant

Amanda Theunissen

Vanessa Thomas

Polly Toynbee

Susie Vereker

Amanda Vesey

Henry Villiers

Mary Villiers

Miranda Villiers

Brigid Waddams

Francesca Wall

Katharine Whitehorn

Victoria Whitworth

Julia Wigan

Fiona Wright

‘This is not a history of women’s boarding schools. It’s not easy to say where, exactly, you would shelve it. It could be under memoir. Or is it more like anthropology? . . . The other option would be comedy, as it’s the funniest book you’ll read all year.’ Nicola Shulman

‘Probably my book of the year’ Rupert Christiansen

‘May I say how delighted I am . . .’

‘I have just received the three volumes that I ordered, Mr Tibbits’s Catholic School, Terms & Conditions and The Real Mrs Miniver. May I say how delighted I am with both the production and the...

Read moreA Chat With Ysenda Maxtone Graham

Read moreNovember News: Old Girls & Very Old Girls

Read moreEar Trumpets & Alternative Bestsellers

Not surprisingly, the highest selling novel was Robert Harris’s Conclave, but the splendid dark horse has been Ysenda Maxtone Graham’s Terms & Conditions: Life in Girls’ Boarding-Schools,...

Read moreYsenda Maxtone Graham on Radio Gorgeous

Read moreOld Girls and Very Old Girls

I went to a girls’ boarding-school in 1972. It was only for an afternoon. I’d been staying with a friend for half-term and we stopped on our way into London to drop her older sister back at...

Read moreThe Slightly Foxed Bestseller!

Read moreHooray for School!

Read more‘This is not academic writing or journalism – this is storytelling . . .’

‘Maxtone Graham’s book – with, I should add, my favourite title of the year; I love an artfully-constructed pun – is rigorously unacademic. There is no index, and there are no footnotes . . .

Read moreThe Captive Reader: ‘Every December, I attend an Old Girls reunion . . .’

‘Every December, I attend an Old Girls reunion and Christmas carol service for my old school. It’s a fun event and I always meet the most interesting women. There’s the Olympian with stories...

Read more

This vivid study of life at girls’ boarding schools between 1939 and 1979 is both hilarious and poignant, finds Maggie Fergusson.

Women who have been to boarding schools,’ writes Ysenda Maxtone Graham, ‘live with flashbacks both joyous and nightmarish.’ reading this hilarious, poignant study, I had two. The first was of a thunderstorm during which our headmistress, Mother Bridget, summoned the school to the concert hall to read Act 3 of King Lear: an act of inspiration. The second was of yawningly dull weekends, when our only occupation was to ‘report’ hourly to the nun on duty. Some girls on the nun’s list had ‘G’ by their names. This meant ‘Greasy’ and allowed them to wash their hair twice a week.

In creating this ‘patchwork of twentieth-century boarding-school life’, Miss Maxtone Graham has spoken to scores of old girls. Some were at school way back in the 1930s and all had left before the advent of the duvet—which ushered in a new warmth and cosiness—in about 1979.

Her writing is crisp, every word precisely weighed. She never tells us what to feel, but simply presents her evidence and leaves us to gasp (often), laugh or, sometimes, cry. She finds gems in old prospectuses (‘the entry of all examinations is purely optional’), clothes lists (‘woven knickers’) and letters home. Here is Amanda Graham writing from Hanford in 1972: ‘We have super lessons today. reading, handwork, handwork, then the rest of the day is free.’

Hanford was a merry school. Girls brought their ponies and there were ‘galloping matrons’ to take them riding. However, most schools had no ponies and minimal merriment. Many were run by cardiganed spinsters, who felt it imperative to keep things comfortless and emotionally austere. Girls spent their free time straddling radiators to try to get warm, the food was foul and, apart from odd-job men, there was strictly no male company.

With the notable exception of Cheltenham Ladies’ College, academic standards were pitiful. When Frances Dove founded Wycombe Abbey in 1896, she promised that ‘the hours of study will be strictly limited’ and the belief that female braininess was unattractive persisted to the middle of the 20th century and beyond. At St Mary’s, Wantage, girls who went to university were so rare that they had their names emblazoned in gold letters in the hall. When Miss Maxtone Graham asked a group of Hatherop Castle old girls whether their school had had a lab, they thought she meant a labrador.

How can parents have chosen such schools? Often, they never even visited, but were charmed by some odd quirk in the prospectus—that the school had looms (St Mary’s, Wantage) or that Elgar had once leapt over the bird bath (Lawnside). Even when they did visit, their reasoning was eccentric. Camilla Geffen’s father chose Heathfield because the girls had no spots.

What parents wanted for their daughters was a suitable marriage as soon as possible after school; further education of any kind was discouraged. Diana Copisarow was only allowed to do a secretarial course ‘in case I married a rotter’.

So what became of them all? Many did marry young. Most had brought up their children before turning 40 and then threw themselves into good works. If this sounds bleak, it’s not necessarily so. In a bittersweet, final chapter, Miss Maxtone Graham argues that the rigours and privations of boarding schools gave their girls enviable qualities. They are resilient, unselfcentred, unspoilt; they look after one another.

Even the dim teaching had its silver lining. Many have gone on to do Open University degrees, join choral societies and subscribe to the Times Literary Supplement. If there’s one thing their education gave these girls, it was ‘a lifelong thirst to improve it’.

New book on girls and boarding, pre-duvets . . .

Women who have been to boarding schools,’ writes Ysenda Maxtone Graham, ‘live with flashbacks both joyous and nightmarish.’ reading this hilarious, poignant study, I had two. The first was of a thunderstorm during which our headmistress, Mother Bridget, summoned the school to the concert hall to read Act 3 of King Lear: an act of inspiration. The second was of yawningly dull weekends, when our only occupation was to ‘report’ hourly to the nun on duty. Some girls on the nun’s list had ‘G’ by their names. This meant ‘Greasy’ and allowed them to wash their hair twice a week.

The mysterious and dreadful – and horribly funny – world of mid C20th British girls’ boarding schools revealed with relish and intelligence by a former inmate. Many women were interviewed about their experiences, including Elizabeth Butler-Sloss, Arabella Boxer, Josceline Dimbleby, Tanya Harrod, Michaela Reid, Cicely Taylor, and Valerie Grove; from their accounts Ysenda has pieced together a detailed and sensitive account of a variety of schools, ranging from hell-holes to little idylls.

There is many a fearful joy to be snatched from the book – a school chosen “for reasons of gravel soil and bracing air”, or simply because it was near a racecourse. The skin on a pink blancmange is remembered by one of Ysenda’s interviewees as “so thick it was like a floor-covering”. Wondering which period to focus upon, Ysenda in the end chose a range from within living memory to “the advent of the duvet”, indicative itself of the privations to which so many had to accustom themselves – icy dormitories, appalling food, pettyfogging rules, iron-grey staff. These leave enduring marks that the author can spot at a hundred paces, a certain “inner toughness, a lack of self-pity”, let alone the curve of a calf walloped into shape by lacrosse sticks. And as for the schooling itself, the general view was that too much education could only mar a girl’s marital chances so best keep it to a minimum.

This sort of schooling brings the first paragraph of Cold Comfort Farm to mind: “The education bestowed on Flora Post by her parents had been expensive, athletic and prolonged; and when they died . . . she was discovered to possess every art and grace save that of earning her own living.” How wonderful that so many of the interviewees defied this rule too.

Dear Ysenda, Your book is an absolute triumph! I have been away and I was thrilled to see my copy had arrived when I returned home yesterday. It is extremely amusing. I have laughed a lot.

My sister was Headmistress of St Felix, so I told her about the comments in your book about the school and she has ordered a copy today. She has to speak at a St Felix dinner on Wednesday and is going to flag up the book and the comments about Miss Oakley, the Headmistress, which she thought were very funny.

I am going to recommend to St Leonards Seniors that they ask their children for a copy of your book for Christmas. Anyone associated with girls’ boarding schools cannot help but be very entertained by what you have written.

Congratulations on a very successful publication. I do hope it does very well.

The unsentimental education of the English girl in pearls . . .

Ysenda Maxtone Graham delights in the jolly-hockey-sticks world of girls’ boarding schools — where the chief lesson learnt was how to survive a dull marriage

If you were to take a large dragnet and scoop up all the shoppers in the haberdashery department of Peter Jones in Sloane Square, your catch would be a group of women of the kind given voice in this marvellous little book. Readers old enough to remember Joyce Grenfell will know the type.

Ysenda Maxtone Graham characterises them as people who sleep with the window open in all weather; who know how to cast on and off in knitting; are thrilled by the arrival of a parcel, even if it’s just some Hoover bags bought on Amazon. They haven’t done up their kitchens since the early 1970s and they always feel homesick on Sunday evenings, even though they’re at home. The mainstays of Riding for the Disabled and the church flower rota, they have names like Bubble Carew Pole and Gillian Charlton-Meyrick. The word gumption doesn’t appear in these pages, oddly enough. But that’s what comes to mind: these women have gumption.

It may seem almost absurdly niche, but this is a book which deserves a wider audience than its title suggests. Like Dear Lupin and its sequels, it finds comedy and a touching sort of home-grown courage in the rather narrow social group it describes. Ysenda Maxtone Graham has an eye for the drollery of detail and an abundance of wit, which helps. She is good at keeping a straight face. Describing the horrors of school food, she writes: ‘Putting pilchards into one’s pocket was a risky business.’ When interviewing one cluster of women whose school had been especially lax, she asks if, between apricot crumble and hockey, they’d had any afternoon lessons, or learned anything much: ‘They weren’t sure but thought probably not.’

Apart from Cheltenham Ladies’ College (always a bastion of intellect), many of the schools were pretty hopeless. There was folk dancing and needlecraft and lacrosse, but most of the teaching staff had not been to university. Science was especially scant: as Nicola Shulman notes in her very funny introduction, the word ‘lab’ meant labrador, not laboratory. This didn’t matter too much, since the schools were essentially holding-bays in which to keep the girls during those awkward years between pony club and getting married. Indeed, one might posit a strong causal link between the demise of such establishments and the burgeoning divorce rate. What better training for long-haul marriage could be devised? Kindness and service to others were inculcated. Girls learned to put up with being cold and with sharing a bedroom; they learned to forgive the bathroom habits of their fellows. Soppiness was to be discouraged; tedium borne. ‘Boredom was really the essence of our existence,’ recalls one former pupil, ‘I actually resorted to reading Solzhenitsyn and Henry James: you have to be very bored to read Henry James, in my opinion.’

Say what you like about internet porn, at least today’s young people know roughly what goes where. For these young women, sex was ‘(a) purely a medical matter and (b) dangerous’. Even regarding their own bodies, information was in short supply. Artemis Cooper found a packet of white shiny pads in her drawer at school and thought, ‘How useful! I’ll use those for cleaning my shoes.’

All of this is amusing, but the occasional glimmers of racism and exclusion are not. Snobbery was rife. The headmistress of St Mary’s, Ascot, began a Latin lesson with this ice-breaker: ‘Now, hands up those of you whose house is open to the public.’ The young Judith Kerr (author of the children’s masterpiece The Tiger Who Came to Tea) had left Germany in 1933. At boarding school, she was asked whether she was a Cockney, ‘because we’ve all been discussing it and we’ve decided your vowels aren’t pure’. One dark-skinned old girl met up with a schoolfellow years later: ‘It wasn’t that we didn’t like you: we just didn’t know what to do about your skin colour.’

Such examples are mercifully rare. Mostly these pages abound in memories of chilblains and the waft of overcooked cauliflower, of hard loo paper and hymn books and linoleum. Teachers wore long cardigans over their shelf-like bosoms and had nicknames like ‘Jellybags’ and ‘the Turnip’. The girls under their care seldom saw a Bunsen burner or even attempted maths O-level, but many of them grew up to be pillars of the community — loyal, courteous and stoical. They’re a dying breed, now. Terms and Conditions is a fitting tribute.

The cruel teachers. The pashes on other girls. The gossip. The giggles. The awful food. The homesickness. The friendships made for life. The shivering cold. Games of lacrosse, and cricket.

The girls’ boarding school! What a ripe theme for the most observant verbal artist in our midst today – the absurdly underrated and undersung Ysenda Maxtone Graham, who has the beadiness and nosiness of the best investigative reporter, the wit of Jane Austen and a take on life which is like no one else’s. This book has been my constant companion ever since it appeared a few months ago.

Schoolmistresses have two kinds of chest. They have either ‘bosoms out to here’ (vast and shelf-like) or ‘bosoms down to here’ (sagging and fleshless). Bosoms are always a source of fascination for growing schoolgirls. No wonder the women who confide their boarding-school memories to Ysenda Maxtone Graham in this exuberant book invariably begin their reminiscences of teachers with the instantly definable bosoms.

I cannot resist writing as like Nicola Shulman I too went to the Mitford Colman school in I suppose 1947 which is a bit of a giveaway! One of my classmates was the actress Anna Massey. The two Mitford Colman sisters, one large and fluffy and the other bone thin were terrifying to someone who had never been to school and been taught by her mother the subjects we both enjoyed from Our Island Story, and A Child’s Garden of Verses and botany. My undoing was custard – we first ate in a British Restaurant in Eaton Square, don’t ask, and then at the school. I still go green if custard appears. I was rescued when the Francis Holland reopened nearby. I am looking forward to reading the book!

Rating: *****

If you think the St Trinian’s films were fictitious, then this wonderful book will surely convince you that they were documentaries. In 1945, the nine-year-old Caroline Cranbrook was sent away to a girls’ boarding school called Wings.

The headmistress was a heavy drinker; when the girls were doing ballroom dancing on a Saturday night, she would sit drumming her fingers with a cigarette hanging out of her mouth and a glass of creme de menthe in her hand.

The girls had to dance with her father, who had lost both his arms in the war: sometimes, his empty sleeves would be pinned on to the girl with whom he chose to dance.

The school sport was rugby. The headmistress loved the rough-and-tumble. ‘Jump on me, girls, jump on me!’ she would say.

Soon, the teachers began to drift away. Instead of replacing them, the headmistress got the senior girls to teach the juniors. Aged 15, Caroline was in charge of teaching biology and geography. Another of her duties was to catch children – some as young as five – who tried to run away down the mile-long drive.

When the school inspectors were due, the headmistress made her put on make-up, so as to look old enough to be a teacher. The school eventually closed in the early Fifties. ‘It was rumoured that the headmistress had knocked out a girl’s tooth in assembly, when she didn’t like the way she was looking at her,’ reports the author.

You might think that this was a one-off case, and no other school could have been quite as peculiar as Wings. But far from it: by modern standards, virtually every girls’ boarding school in Britain was completely batty . . .

Read more

Every December, I attend an Old Girls reunion and Christmas carol service for my old school. It’s a fun event and I always meet the most interesting women. There’s the Olympian with stories about her time in Brazil this summer, the children’s book author who I adored growing up, the researchers doing amazing work in their labs, and the retirees who now travel the world after lives spent in law, medicine or academia. It’s a circle I take for granted much of the time but always appreciate reconnecting with around the holidays. It is also a chance to cuddle babies of younger alum while eating cookies with the school logo on them – a win-win, really.

This year, the event was the perfect thing to get me in the mood for the newest release from my beloved Slightly Foxed (so popular they are now out of stock and waiting for it to be reprinted): Terms and Conditions by Ysenda Maxtone Graham, a history of British girls’ boarding schools from 1939 to 1979. The cut off date is, delightfully, based on when the duvet became popular, ushering in an era of unprecedented comfort. Maxtone Graham is having none of that: “the years I longed to capture were the last years of the boarding-school Olden Days – the last gasp of the Victorian era, when the comfort and happiness of children were not at the top of the agenda.” And capture it she does, in vivid, joyful detail . . .

It’s no surprise that Terms and Conditions, Ysenda Maxtone Graham’s book about girls’ boarding schools, appeared in the Christmas stockings of quite a few Good Schools Guide writers, but despite its rather niche subject matter this beautifully produced little book has also been something of a hit with the wider reading public.

Ms Maxtone Graham defines her book’s parameters very carefully, claiming one of the main reasons 1979 is the cut-off point for her study is because it was ‘the advent of the duvet’. That 30+ year buffer also provides protection from any accusations of promoting or indeed libelling the featured schools, many of which are still going strong today.

The joy of the book – and the sadness – comes from the voices of former pupils. The author lets them tell their own stories of war time deprivation, benign (and savage) eccentricity, devastating homesickness, petty rules and educational anarchy. Letters home were censored, bullying and social snobbery went unchecked; girls were used as unpaid labour – mopping floors and cleaning windows under the guise of learning domestic skills. This went on in even the most exclusive schools (‘You mustn’t ask a housemaid to do a job if you yourself don’t know how it’s done’).

Schooling for girls was not considered as important as it was for their brothers (several of Maxtone Graham’s older interviewees came from families who had hitherto employed governesses). The belief that ‘too much education’ rendered women unmarriageable persisted, even into the 1960s, and little attention was paid to the academic credentials of a girls’ school. Maxtone Graham recounts how fathers would choose boarding schools for their daughters on the basis of social, rather than academic reputation, believing that spending a few years in an Elizabethan manor house would be sufficient to prepare them for a good marriage. With a few pioneering exceptions such as Cheltenham Ladies’ College most girls’ boarding schools did not expect their pupils to go to university. Even fewer taught science – there were no laboratory facilities, not even a Bunsen burner, at some schools until the 1970s. It’s painful to read some of the stories of thwarted ambition and unrealised potential.

Some former pupils pay tribute to inspirational teachers (very often English teachers) and the tireless dedication of ‘spinster’ headmistresses; others still shudder at the tyranny of enforced team games. What comes across most strongly is the resourcefulness, resilience and lifelong friendships that came out of frozen hot water bottles, terrible food and sitting on radiators ‘planning subversive things to do’.

What fertile – if disturbing – ground these schools would have been for Good Schools Guide reviewers. Terrible food (that had to be consumed with perfect table manners), freezing dormitories, persistent running away and, as a consequence of the latter, corporal punishment. But was something lost when so many small schools finally ‘faded away’ in the 1980s? Perhaps. As Maxtone Graham puts it: ‘The worst of the hopelessness has gone, but so have the best of the eccentricity and the most well-meaning of the amateurishness.’ And some things endure – school slang and quirky traditions, old-fashioned uniforms, wonderful camaraderie but not, we hope, the chilblains.

This is not a history of women’s boarding schools. It’s not easy to say where, exactly, you would shelve it. It could be under memoir. Or is it more like anthropology? . . The other option would be comedy, as it’s the funniest book you’ll read all year.

‘A rich read . . . Ysenda Maxtone Graham has drawn aside the curtain on the hermetic, arcane world of the mid-20th-century girls’ boarding school, which we all believed to be weird, but few of us – unless we were there – realized was as eccentric, hilariously funny, cruel, terrifying, snobbish, rapturous and emotionally intense as the profoundly outlandish environment portrayed in these pages . . . Terms & Conditions is a funny, vivid and excruciating book, which has left me filled with admiration for the brave, damaged survivors of this lost world.’

This scintillating history of the mid-twentieth century girls’ boarding school . . . is not, it should immediately be said, an orthodox history. Maxtone Graham did her research not by talking to educationalists but by sitting down with a tape recorder at a series of meetings arranged for her by confiding old girls . . . The advantages of this approach will be appreciated by anyone who has ever yawned his, or her, way through an official school history where whatever the pupils may have thought of their experiences usually takes a back-seat to the restoration of the chapel . . . As might be expected, the real charm – and some of the horror – of Terms & Conditions lies in its incidental detail . . . No disrespect to the shelf of up-market novels that has come my way since January, but this is by far the most entertaining book I have read this year.

Ysenda Maxtone Graham, alumna of the King’s school, has interviewed a host of famous women to recount the ramshackle atmosphere of girls’ boarding schools in this elegant book. . . . Academia was shunned in favour of domesticity – for example, making a bed with ‘hospital corners’, running away was the norm, with one girl hiring a chauffeur- driven Daimler for the occasion. Another escaped to her godfather who lived at the savoy. Their stories are tinged with eccentricity and romanticism: prepare for a madcap dash to a bygone era.

My favourite title of the year . . . There is a touching exuberance throughout Terms & Conditions that made me love every moment. This is not academic writing or journalism – this is story-telling, and Terms & Conditions is all the more enjoyable for it . . . It’s a perfect stocking filler . . . This one will have you or your loved one giggling all through Boxing Day, sharing anecdotes and marveling at the extravagances both of youth and of recollections of youth.

You know how much I hate to use the Ch*****as word before December 1st, but needs must if we don’t all want to find My Life by A Celeb under the tree, so I make an exception each year with a few posts about books that have arrived and which you might want to add to your list, so you can be ready when people ask the fateful question.

…or perhaps you are looking for ideas for gifts for others.

Well, an absolute gem was waiting for me as I staggered in the door laden with books from London and it is right up our street….

‘When I asked a group of girls who had been at Hatherop Castle in the 1960s whether the school had had a lab in those days they gave me a blank look. “A laboratory?” I expanded, hoping to jog their memories. “Oh that kind of lab!” one of them said. “I thought you meant a Labrador.”’

I didn’t mean to start reading it immediately because I had that pile of new books just bought, but really, if this arrived in your stocking, it would make the very best Boxing Day read. I’d just browse a couple of pages I thought. 226 pages later I’ve almost finished it so will just have to hope for something else to fill Boxing Day.

We have had many boarding school conversations on here in the past, usually in the wake of books about St Bride’s by Dorita Fairlie Bruce or the Chalet School, or most recently and worryingly idyllic The School on North Barrule by Mabel Esther Allan

So many schools, so many Old Girls, ‘ muses Ysenda, as she drives away from her first interview, before deciding on a start and cut-off date for her book. Settling on from ‘in living memory’ to the ‘advent of the duvet’ which, with its connotations of warmth and comfort, gives you some idea of the discomforts suffered and recounted herein and often in the sort of detail that makes you want to head for the nearest blanket…

‘We did all our lessons wrapped up in rugs with mittens on…’

‘Evacuated to Chatsworth in the war, Nancie Park picked her hot-water bottle off the floor in the morning and found it was a solid lump of ice.’

Raised on the glories of Malory Towers (which I now discover was based on Benenden as attended by Enid Blyton’s daughter) and feeling sure that Darrell Rivers would be my friend and I would excel at lacrosse, I can’t have been the only 1950’s girl begging her parents to send her to boarding school. Had my parents had a mind to oblige there were probably still plenty to choose from in the south of England alone. In the 1930s, 16 in St Leonards, 22 in Malvern, 23 in Eastbourne, 32 in Bexhill-on Sea and about 150 in Surrey.

‘Harsh matrons, freezing dormitories and appalling food predominated, but at some schools you could take your pony with you and occasionally these eccentric establishments – closed now or reformed – imbued in their pupils a lifetime love of the arts and a real thirst for self-education. In Terms & Conditions Ysenda speaks to members of a lost tribe – the Boarding-school Women, grandmothers now and the backbone of the nation, who look back on their experiences with a mixture of horror and humour.’

Judith Keppel (you know the first one to win Who Wants to be a Millionaire and now part of the TV quiz team Eggheads) recounts her greatest fear whilst attending St Mary’s, Wantage, a school run by Anglican nuns and chosen by her parents because it did weaving; a room full of looms seeming slightly out of the ordinary…

‘Judith was terrified of getting ‘The Call’. ‘We all knew about the previous headmistress, Sister Mary Patricia, who had been young and pretty with a life of fun ahead of her – and The Call came to her like a thunderbolt. She couldn’t escape it. She went twice around the world to try to escape it, but to no avail. To me, that was a fate worse than death.’

There are tales of humiliation and homesickness…uniform that wasn’t quite uniform the source of much self-conscious embarrassment; the homemade versions that would invite derision and a sense of exclusion. But the idea of the ‘lost tribe’ rings so true, camaraderie in adversity much in evidence and this little book a real gem of a tribute to them all. As Nicola Shulman suggests in her preface…

‘This is not a history of women’s boarding schools. It’s not easy to say where, exactly, you would shelve it. It could be under memoir. Or is it more like anthropology? . . . The other option would be comedy, as it’s the funniest book you’ll read all year.’

It is indeed a funny book… especially when you read that the gristle and slop that passed for boarding school food, (and approached with exquisite table manners) was the perfect training if you were likely ‘to finish up in a gulag.’

But Terms & Conditions has a serious side too….

Like many who read here I too was part of that generation educated by the ‘Misses’ who, consigned to spinsterhood by the wartime depletion of suitors, turned their attentions to teaching. Now some of them were wonderful, we often talk about those who inspired us here, but there were some sadists among them (many named in this book ) for whom emotional and physical abuse were second nature and who would now find themselves very much on the wrong side of the law. That sense of education by fear most definitely reminded me of my primary school head mistress, Jessie Horsburgh, a devout but fearsome woman, as wide as she was tall to my young eyes, and also capable of inducing gut-wrenching fear and inflicting much physical and emotional pain. We were certainly not spared in the state sector but at least we had some kind teachers (also terrified of her) and went home to loving parents (even more terrified) at the end of each day. For these poor girls at boarding school there could be no respite and heavens did they suffer, for many this was a very expensive and torturous imprisonment and with very little useful education to show for it on escaping leaving.

A note about Slightly Foxed editions, small but perfectly formed and cloth-bound, these are books to keep and collect, you would definitely want to find this one in your stocking on Ch******as morning.

And talking of lacrosse…did anyone else play it ?

We did, very briefly at Nonsuch Girls (not boarding and a joy in comparison to my primary school) but I think we all got completely carried away with the no boundaries thing and were running wild (probably into Cheam village, any excuse) so it was stopped. Miss Dormer soon had us called to heel with her Acme Thunderer and confined once more within the lines of the hockey pitch.

Sprinkled with reminiscences from a bygone era that are both poignant and laugh-out-loud funny. This book would make the perfect Boxing Day reading material, so be sure to add it to your Christmas list!

Dormitory Stories

Boarding schools, as J.K. Rowling can attest, are an excellent means by which the writer of children’s fiction can dispose of parents. The self-containment of a boarding school, often in rural isolation, its hierarchies, bells, houses and stupefying rules are the perfect background for heated friendships, weird, sometimes vicious, authority figures and the subversive heroes who outwit them.

Ysenda Maxtone Graham’s new book examines the hundreds of real-life girls’ boarding schools that flourished in the mid twentieth century, from the outbreak of the Second World War to the late 1970s. In their hermetically sealed worlds, life was often stranger than anything a novelist would dare dream up. From the perspective of our current anxiously league-tabled, exam-orientated, educational expectations, it seems extraordinary that some of these schools, run by women with no qualifications and often eccentric theories of child development, should have existed at all. But they make for some wonderful stories – and anyone, like me (Woldingham 1974-1981), who ever attended a girls’ boarding school will gasp with instant recognition.

Former pupils remember as yesterday the smells of polished parquet, cleaning fluid, gymslips washed only once a term, libraries (havens for the homesick) and over-boiled stodge. Everyone recalls those ubiquitous thick gym knickers – a feature of school life well into the 1970s – to say nothing of the regulation Izal medicated loo paper. The schools were not just about classroom education – in most, very little about it – but in the days before parents could stay in constant electronic contact with their daughters, they were substitutes for home. The responsibility was awesome and subject to sometimes idiosyncratic interpretation. Maxtone Graham has trawled prospectuses with their promises of bracing air, well-maintained parkland or stabling for ponies. Schools brought their own distinctive features to the requirements – compulsory folk-dancing, for example, bell-ringing or animal husbandry. Girls’ education being seen by most pre-war parents as preparation only for light secretarial work then marriage, schools’ selection was often whimsical. St Mary’s Wantage was chosen because it “offered weaving”; another school because “none of the girls had spots”.

“School spirit” gusted through the curriculum, along with exhortations about “getting a grip” or “grasping the nettle” – though to what purpose was sometimes harder to discern. “I sometimes speak about the dry rot of slackness,” wrote Miss Baird to new girls at St James’s Malvern in the 1930s. Competitiveness was traditionally reinforced by houses, shields and team games. Teachers were free to indulge arbitrary obsessions – sometimes inspirational, quite often alarming. At Cheltenham Ladies’ College, pupils were left none the wiser in religious studies: “Miss Popham went on and on about how the Philistines’ foreskins were cut off and put into sacks.”

Men were rarely glimpsed and therefore tremendously exciting. At St Leonards in the 1960s, a local barber, the “Hairy Man”, washed the girls’ hair once a week, and at Hatherop Castle pupils lowered articles of underwear from a dormitory window to “VBs” (Village Boys) in exchange for bottles of cider. Romantic yearnings were channelled into intense “pashes” on older girls. By the 1970s, yearnings had more outlets (in our case, Starsky and Hutch on the tiny common-room telly – which of them were you going to marry?) but sex education was non-existent or confusing. At St Mary’s, Ascot, girls received mystifying instructions on remaining a clean hardback book rather than becoming a dog-eared, second-hand paperback.

There was a great deal of doing nothing: “Boredom was really the essence of our existence.” Hours rolled by sitting on radiators (despite dire warnings of piles), practising fainting, experimenting with Ouija boards or playing jacks. One girl spent a term making the Antarctic out of polystyrene. Memories of bullying, however, still chill the blood. Teenage girls’ friendships were (are) often painfully emotional and exclusion and cruelty were rife. The full immersion of boarding intensified relationships to boiling point. At Downe House in the 1950s, there was a divorce room to which girls would be summoned only to have their “friends” ritually walk out.

A chapter on convents includes many anecdotes of social snobbery. Nuns were not necessarily more snobbish than lay schoolmistresses – it was rampant everywhere – but convents are of their time too. In my experience of Woldingham, however, then the Convent of the Sacred Heart, in those years after Vatican II, snobbery was left behind with the old guard. The nuns who taught me caught the new spirit with gusto – and were in their way feminists of a type unfamiliar in most girls’ schools: proponents of a radical, communal, non-domestic option. I think too that we would have seen, if we had chosen to, that teaching privileged private-school girls might not always have been the most rewarding way to live out a vocation in the 1970s.

With her bright, generous wit, Ysenda Maxtone Graham is exactly the right person to write on this subject. The author of, among others, a portrait of the Church of England (The Church Hesitant), she has a genius for peering beneath English gentilities to reveal surprises and contradictions. No detail escapes her: inventive nicknames, for example (Jellybags, Kipper, Moo, Turnip, Wopsy and Farto among them), or headmistresses’ taste for bracing Capitalisation – “Massed Drill and Dancing Displays followed the Garden Party and a short, informal Concert was given by Old Penrhosians.”

It is never nostalgic, but this is not a debunking book – in fact it can be viewed as a quiet celebration of the educative possibilities (up to a point) of oddball ideas, and the resourcefulness that can be nourished by lots of loafing about. As I am sure any novelist would agree.

This book is just too true and it was interesting to read that our school in Eastbourne (The sun trap of the south) was not just one of a kind. I was “educated” in the ’50s and left at just 16 with two 0’levels. I did a secretarial course, it was that or nursing. Worked for a couple of years and then on the day after my 20th birthday married my school friend’s brother, as one does.

Terms and Conditions brings it all back, we had stodge, jacks, cold radiators, unskilled staff and hymn singing on Sunday nights. My time was spent either doing sport or punishment; I don’t remember much learning. I suppose out of sheer boredom I was constantly in trouble. I can quote endless bible passages and poems having had to learn them on a Saturday night instead of dancing to 78 rpm records on the wind up gramophone. Read this book and be grateful that things have moved on and changed for the better.

Very disturbing. This book makes me grateful to have attended a day school.

Thank you for your comment, Sue. There certainly are some interesting tales from boarding schools!

Just to say, I thoroughly enjoyed reading Terms & Conditions, it really brought back many memories of boarding school in the late 1950s/’60s and I have gone back again and again to the book. Have now been in touch with the boarding school that I went to and hope to catch up with old school friends.